In 2021, wealthy countries doled out third doses of vaccines against COVID-19 while the disease surged in parts of the world that had none. Had vaccines been more equally distributed, an estimated 1.3 million people might be alive today, and the delta and omicron variants that exploded during those surges might have fizzled out before spreading around the globe.

Had vaccines been more equally distributed, an estimated 1.3 million people might be alive today

The most exclusive and arguably most effective COVID-19 vaccines in 2021 used messenger RNA (mRNA). Rather than rely on charity in the next epidemic—a fool's errand time and again—countries that had almost no access to mRNA vaccines launched an initiative in June of that year led by the World Health Organization (WHO) to make their own. Unlike earlier efforts to produce vaccines in the low- and middle income countries, the WHO mRNA technology transfer hub put the technological platform before the disease. The vision was for companies and institutes in 15 middle-income countries to produce mRNA vaccines for their own regions.

Demand for COVID-19 vaccines, however, has dwindled, and no other mRNA vaccines have come to market, meaning that the WHO hub remains more potential than proof of concept. That observation does not demean the effort. The future appears full of opportunities if the hub can overcome technological, economic, regulatory, and other challenges.

Targets and Technology

Biotechnology analysts predict that mRNA will become the dominant vaccine platform over the next 15 years, with candidates against HIV, rabies, seasonal influenza, Chikungunya, and other pathogens in the pipeline. At an event about the WHO hub, Drew Weissman, who won a Nobel Prize for his foundational work on mRNA vaccines, listed diseases ranging from cancer to sickle cell anemia that mRNA vaccines and drugs could address. He encouraged hub leaders to move forward and emphasized that for "local regions to develop the therapeutics they need, they have to have access to the RNA scientific technology."

Producing mRNA vaccines involves chemical-based processes rather than finicky steps in large bioreactors or expensive, high-level biosafety containment laboratories, making the mRNA platform attractive to countries with nascent pharmaceutical sectors. Achal Prabhala, a public health researcher at AccessIBSA in India who serves on the WHO hub’s board, believes that the hub "is a viable, long-term bet because this is the most scalable technology anywhere in the world."

From Imitation to Innovation

Within a year of the WHO hub's launch, researchers at Afrigen Biologics & Vaccines, a small biotech company in Cape Town, South Africa, had developed an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine similar to the one made by Moderna. Afrigen showed the hub's other partners in Argentina, Indonesia, and a dozen other countries how to make it. The countries meet regularly to swap tips on mRNA vaccine production, a notable departure from the typical mode of drug development in which pharmaceutical companies prioritize secrecy to maintain a competitive advantage.

Afrigen no longer plans to take its COVID-19 vaccine through clinical trials for regulatory authorization. At this point, high levels of partial immunity complicate such trials, and the market for COVID-19 vaccines in southern Africa has dried up. Researchers at the company have begun working with the South African Medical Research Council (MRC) to develop mRNA vaccines against tuberculosis and HIV, which have proved challenging for vaccine development in the past. Last year, scientists in the group published a report on proteins that future tuberculosis vaccines might target. The U.S. Agency for International Development recently invested $45 million in the MRC's project to develop proteins that trigger an immune response against HIV and could form the basis for vaccines.

Building the Business Model

Even if South Africa's effort goes well, a decade could pass before such vaccines come to market—a possibility that underscores economic challenges facing the WHO hub. From a business perspective, the hub's Asian partners might be best placed to remain active before another outbreak triggers the need for vaccines. Companies in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam sold other vaccines and drugs before the hub launched. Those companies are sustained by private and government investment and are in or near countries with significant biotech sectors, including China, Singapore, and Thailand.

Even if South Africa's effort goes well, a decade could pass before such vaccines come to market

For example, the WHO hub's Indian partner, Biological E, has made drugs and vaccines since 1962 and currently produces some 50 products. At the peak of the pandemic, Biological E repurposed one of its facilities for mRNA vaccines and applied to be a part of the hub initiative. A spokesperson says the company has gained technological prowess around mRNA through the collaboration, connections with suppliers, and remains up to date on the latest equipment.

Tools are also advancing rapidly. The WHO hub's last gathering showcased a machine from Quantoom Biosciences that automates much of the mRNA vaccine-making process. "This increases efficiency and yield, which brings down the price," says WHO’s vaccine research coordinator Martin Friede. And price matters. Companies need to make and sell mRNA products so that they are around when the next pandemic hits. Some are considering mRNA-based drugs, rather than vaccines. At least a third of some 125 mRNA pharmaceuticals that companies around the world are clinically testing are therapeutics.

Patent Problems and Red Tape

The explosion of interest in mRNA pharmaceuticals is good news for the WHO hub—but not entirely. Most companies working on mRNA are in wealthier countries, often allowing them to move faster and patent innovations along the way. As of June 2023, more than 15,000 patents related to mRNA vaccines have been granted around the world. AccessIBSA's Prabhala says that patents could pose a problem for the hub's partners in Brazil, India, and other middle-income countries where big pharmaceutical companies have fiercely defended their intellectual property.

Governments in those nations could help regional mRNA efforts by examining patent applications more closely or overriding patents that prevent national companies from moving forward in order to protect domestic interests against public health threats. That strategy could take a cue from the U.S. government, which made Moderna's speedy work possible by permitting it to infringe on third-party patents while manufacturing its COVID-19 vaccine. Entities that use intellectual property in this way typically pay royalties to the innovating companies in exchange.

Another way to foster success is to make regulatory processes across low- and middle-income countries more efficient without compromising safety. Large pharmaceutical companies in wealthy countries stand a good chance of developing the first mRNA vaccines in the event of another pandemic. If the WHO hub's partners are ready to make mRNA vaccines, they should transfer their technology rapidly. However, clinical trials on locally made products take months if not years. Prabhala recommends using alternative analyses that prove one mRNA vaccine is equivalent to another, as is done with certain drugs made by generic manufacturers.

Making the Vision Viable

The WHO hub's partners in Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal face steeper challenges because their pharmaceutical sectors are at an early stage, they have more difficulty importing reagents and equipment, and need to grow their scientific workforce. Even in South Africa, Afrigen's Petro Terblanche notes that the slow pace of imports has significantly delayed progress.

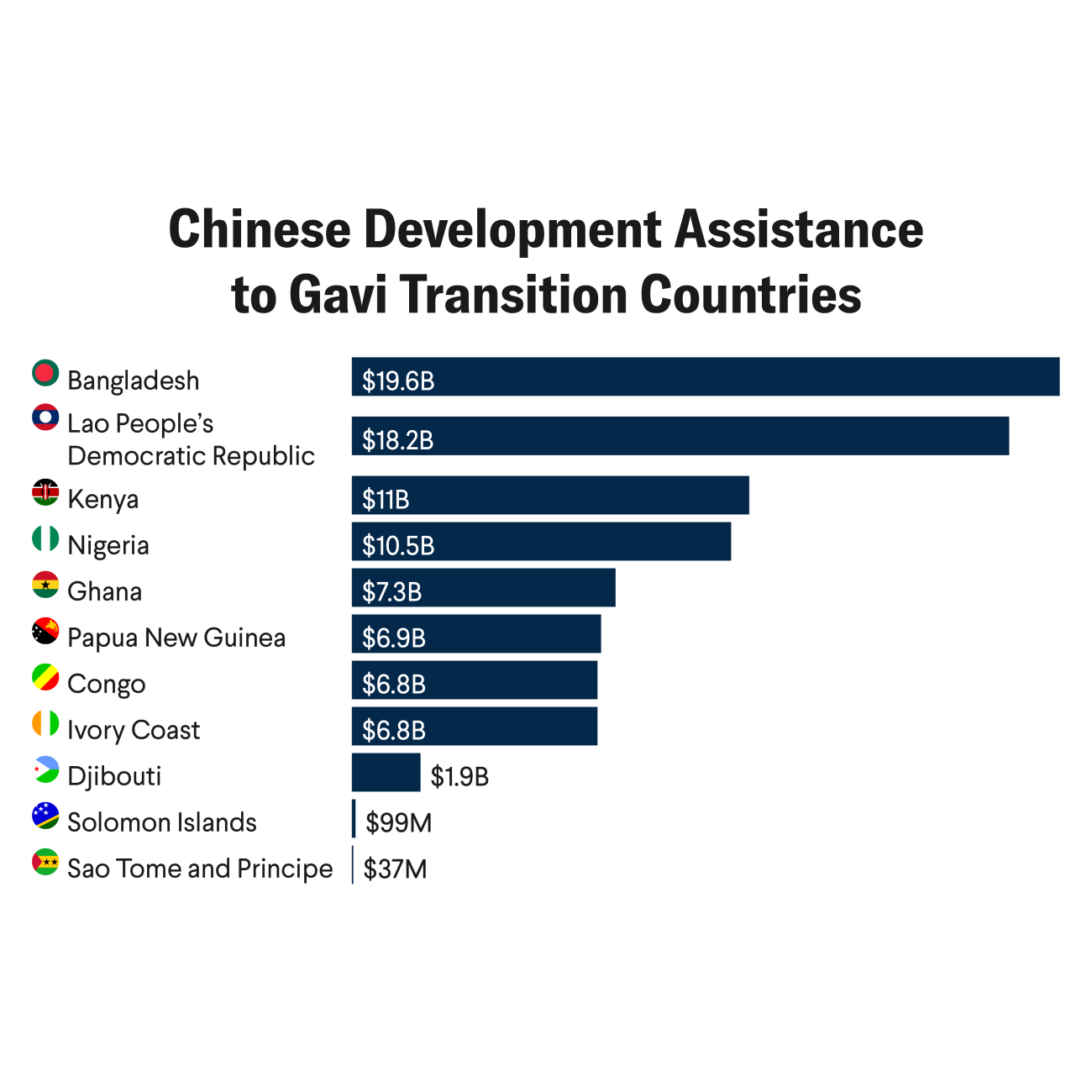

Funders have recognized the need to overcome such obstacles in Africa. The GAVI Vaccine Alliance recently pledged $1 billion to advance the African Union's goal of having at least 60% of vaccines administered in Africa to be made on the continent by 2040. That is a drastic shift from current conditions, where just 1% of vaccines used in Africa are produced there. Such an outcome would address public health problems while boosting economic development.

The vision of the WHO's hub initiative remains to be realized, but its momentum is notable

The vision of the WHO's hub initiative remains to be realized, but its momentum is notable. For example, Afrigen expects to receive regulatory authorization in 2024 to manufacture vaccines from start to finish—a process that typically takes five to seven years for a new facility.

Driven by such national milestones, the hub in South Africa is growing more quickly than efforts by Western companies to help increase vaccine manufacturing on the continent. In 2021, Moderna and BioNTech, the German company that co-produced mRNA COVID-19 vaccines with Pfizer, promised to build African mRNA vaccine plants. But shipping containers from BioNTech meant to house eventual production only arrived in Rwanda last year. Moderna lags even further behind, having recently signed a contract to build its plant in Kenya.

If the WHO hub's momentum continues, emerging economies will move closer to having the capacity to protect their populations from pathogenic threats during pandemics and beyond.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article is the first installment in a series on efforts to increase pharmaceutical production in developing countries guest-edited by Amy Maxmen. The other articles in the series can be found here.