COVID-19 is often described as an unprecedented challenge as a way of explaining why local health systems in the United States were caught tragically underprepared. But unprecedented should not be interpreted as unpredictable. In fact, the outbreak of the novel coronavirus was preceded by several iterations of pandemic preparedness and response plans issued over the last two decades by various government agencies tasked with the health and safety of the American people. Following the emergence of SARS and the re-emergence of H5N1 avian influenza in 2003, the Department of Homeland Security created the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Plan, published in 2005. Within the same year, the Department of Health and Human Services developed and distributed its own Pandemic Influenza Plan. Both were continuously revised and recirculated in the wake of the Swine Flu outbreak in 2009, the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014, and the Zika virus outbreak in 2015. Each updated version of these plans came with urgent warnings to prepare for the next pandemic, and we were given a playbook on how to do so.

We were delayed, we were unorganized, and we were ill-equipped

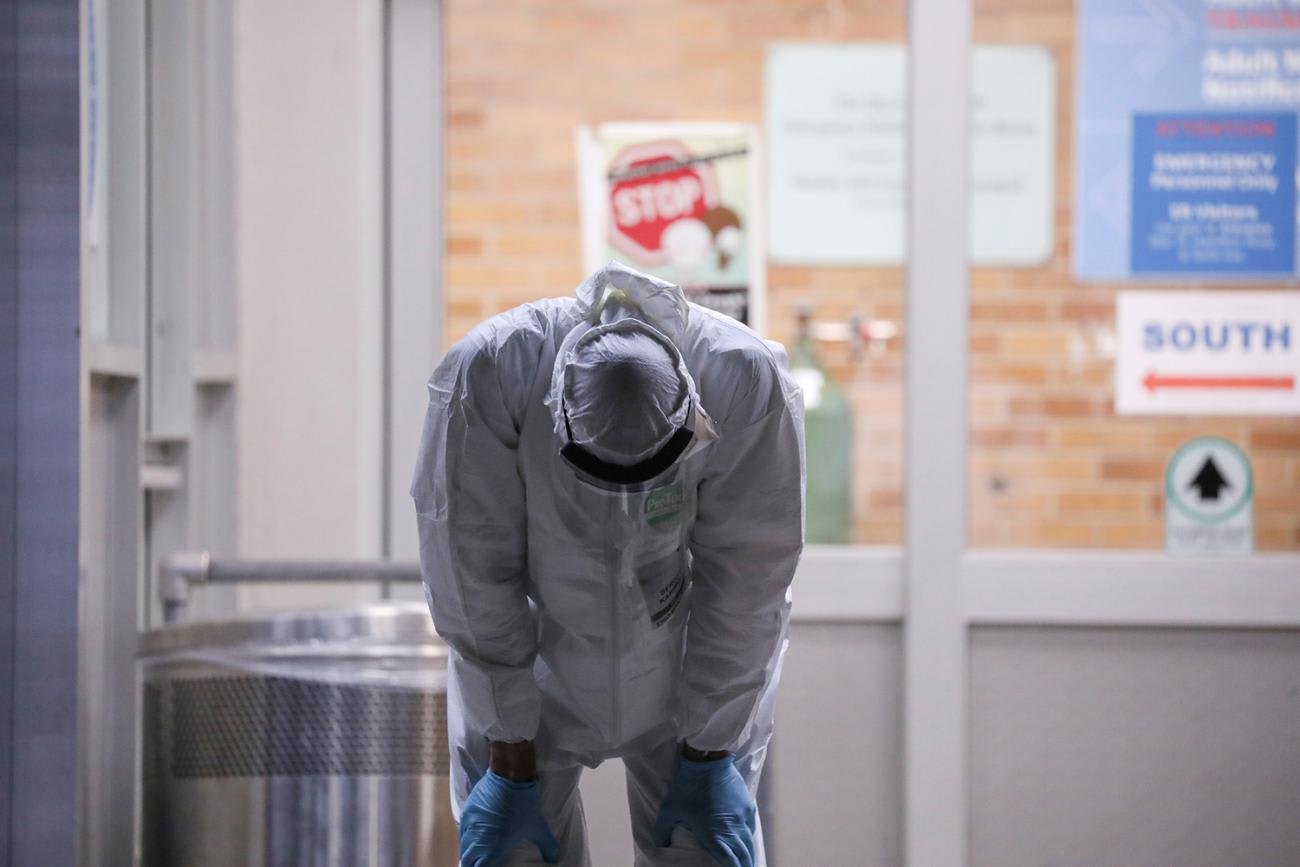

As a member of the Council on Foreign Relations Independent Task Force on Preparing for the Next Pandemic, I have read through every single one of these revisions. Sadly, despite all this painstaking preparation on the part of the U.S. government, our COVID-19 response was impeded by multiple, mostly predictable operational limitations including breakdowns in our supply chain and technical capacity, an underbudgeted and overstretched frontline medical workforce, and fractious and confusing lines of communication among public health stakeholders. These are not failures in planning, but of action—we were delayed, we were unorganized, and we were ill-equipped.

Solutions to the problems we have faced in the recent past with COVID-19 tend to focus on logistical fixes: restocking our national stockpile with personal protective equipment, modernizing and expanding our laboratory facilities, and encouraging rapid vaccine development. Technological advances including innovations in pathogen sampling, health informatics, and telemedicine have also been proposed, and while these are all necessary and laudable pursuits, they do not address a deep foundational flaw imbedded in every pandemic preparedness and response plan I have reviewed. Health care in the United States is rotting at its core.

Health care in the United States is rotting at its core

What COVID-19 has so painfully exposed is a dangerously eroded American health infrastructure on the brink of collapse with the slightest additional burden. Our system has zero slack to combat surges brought on by outbreaks or any other mass casualty event. We have known this for quite some time, and we have put off crucial repairs for far too long. And for COVID-19, it is too late. But there is still a chance to rebuild a health system capable of responding with expediency, efficacy, and equity for the next pandemic. So how do we do that?

This brings us back to the ever-unpopular debate over health care reform. Hard times require even harder conversations, and this is the hard truth: despite the daunting upfront costs, reforming our health system to prioritize primary care represents the most comprehensive, cost-effective approach to best prepare us for the next pandemic.

Reforming our system to prioritize primary care represents the most comprehensive, cost-effective approach to best prepare us for the next pandemic

This is not only what's right for our patients, it is also what's safest for our country. Excluding the social, nutritional, and environmental determinants of health, inequitable access to primary care represents the most significant driver of health disparities in the United States. We have adequate evidence demonstrating how these inequities contributed to reprehensible mortality figures for COVID-19 among our most vulnerable communities—minority communities, undocumented and undomiciled communities, the uninsured and the underinsured. Lacking adequate primary care, these patient populations frequently depend on emergency rooms for medical treatment—or they forego care-seeking altogether. Health equity and health security have been revealed as mutually dependent during COVID-19; by supporting a health system centralized on a primary care model, we can achieve both. It should be no surprise that the task force report recognizes primary care as a central component to strengthening our pandemic response capacity in the United States.

Investing in primary care now will give us a multi-layered return when the inevitable next outbreak occurs, and we can readily project the short and long term benefits. Primary care promotes healthier patient populations by addressing uncontrolled, underlying chronic illnesses, improving baseline resilience to emerging and re-emerging communicable diseases by reducing the number of people who have severe outcomes requiring hospitalization during a pandemic.

A strong primary care system provides a durable base for operationalizing all outbreak response activities

Primary care can also improve our surveillance and disease mapping capabilities, which represent the most effective strategy for averting excess deaths from any novel evolving contagion. When we consider the specific tactics—identification, contact tracing, isolating, and monitoring—widespread implementation of these measures still requires a foundation on which to operate with reliability and rigor. Primary care involves long-term relationships between provider and patients, with physicians working to improve the holistic health of those under their care rather than simply managing diseases. Patients are more likely to speak to a trusted family physician about contacts, where they would shy away from a stranger. They are more likely to believe the need for quarantine from the doctors who have shown through past examples that they are acting in the best interests of their patients. A strong primary care system provides a durable base for operationalizing all outbreak response activities.

The existence of these kinds of patient-provider relationships would have limited the damage incurred by COVID-19. At the beginning of the first surge in New York City, I found myself explaining over and over again to patients whom I had never seen before that COVID-19 was real, and that it could indeed kill you. I had to debunk the conspiracy theories and fraudulent treatments they found on Facebook and Google, which had lead them to act in ways that greatly risked their health, and that of their families.

Unsurprisingly, our most vulnerable communities with little-to-no contact with the health care system, who like all of us were desperate for information about COVID-19, turned to non-medical sources that are replete with misinformation and disinformation.

Now imagine this same scenario, but this time these patients are speaking to a family physician they have seen for many years—a physician who knows everything about their medical history, a familiar face and voice who can easily converse with them without the need for an interpreter, who has seen them and their families through prior illnesses. These patients will believe and follow the advice on COVID-19—from their trusted physician instead of the internet.

This is the most important lesson we should learn from our failures with COVID-19 in the United States

Trust and communication. These are the essential elements—the tools of resilience—that most pandemic preparedness and response plans fail to capture, and these are the basic units built into primary care. We need to get back to these basics. Because imagine during the next pandemic if our best laid plans go awry, if our containment and mitigation measures are unsuccessful, and if we are once again facing socioeconomic instability and fragile government leadership. With careful and consistent investment in primary care now, we will be left with an intact and robust health system predicated on clear channels of communication through strong trust networks—through trusted patient-provider relationships that can guide individuals and communities towards a safer, healthier future. This is the most important lesson we should learn from our failures with COVID-19 in the United States. If not remembered and embraced, we can easily guess and rightfully fear of history repeating itself.