Bibas was a happy and healthy eight-year-old boy living in a small rural village in Mirkot, Gandaki province, in Nepal. One day, as he was playing outside on his rooftop eating cucumber and trying to get some fresh air, he was electrocuted by a low-hanging, live, high-voltage electric wire and gravely injured. His father, a paid driver, was fortunate to have the transportation to make the two-hour drive to Pokhara to access the medical college. Due to a lack of space in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) he was referred to another government facility in the same town. A few hours later, he was transferred to a third facility that could better assist with his difficult case, where he would spend the next three months.

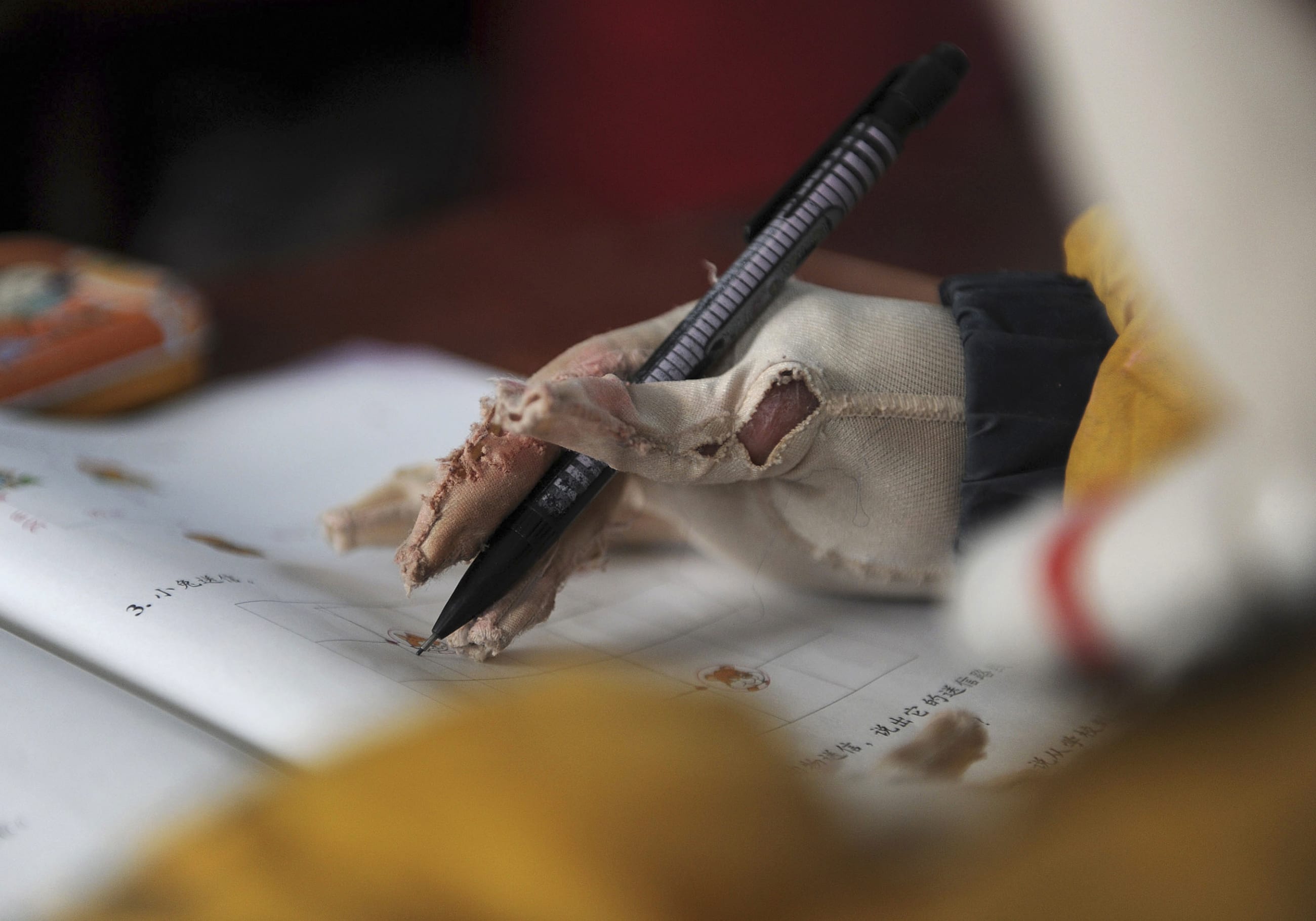

Even though Bibas' family was able to access the care he needed and find a hospital equipped with the necessary surgical teams that could treat the burns, the damage caused by the electric shock could not be reversed. Bibas' right arm was amputated and he sustained severe burns across the rest of his body. He also developed a burn contracture—when a burn scar thickens and tightens, preventing movement—on his left hand that rendered his remaining arm unusable. Once vibrant, he could no longer perform everyday tasks, such as feeding himself or holding a pencil at school, and he had to rely on his mother's help for his day-to-day activities.

Once vibrant, he could no longer perform everyday tasks, such as feeding himself or holding a pencil at school

A month later, Bibas' life changed yet again when he met Dr. Kiran Nakarmi, a ReSurge International surgical outreach partner based in the capital-city Kathmandu, Nepal, who was making his routine visit to the outreach center in Pokhara, six hours away. Dr. Nakarmi was able to perform several complex procedures in a series of burn scar contracture release operations that would restore function in Bibas' remaining hand. The surgeries were conducted over several months, each of these highly technical hand procedures were all worth it in the end. Bibas' arm is fully mobile. He can now feed himself, write with his left hand, and even ride his bike to school. His mother is now able to care not only for Bibas, but also for her other two sons, and can return to the market where she sells vegetables to make a small profit to feed her family.

Unlike Bibas, many burn patients around the world do not have access to immediate care and advanced medical treatments, leaving them to face a lifetime of preventable deformities, disability, dependence, social exclusion, and with few options other than to beg for survival. Recent studies, in Nepal, show that burn-injury victims wait an average of eighteen years to have access to life-changing burn contracture procedures. Dr. Nakarmi reports that in Nepal, through ReSurge International's local surgical capacity building programs, the wait time has decreased under five years for 75 percent of the population. However, 12 percent of the survivors with severe burn injuries still have to wait for more than twenty years on average from the time of their initial burn accident to surgical treatment. This data has been collected at the Kirtipur Hospital in Nepal, which has cared for over 5,200 burn patients over the last fifteen years.

The problem of increased prevalence of burn injuries in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is compounded by the lack of access to appropriate treatment and basic wound care. Many health-care facilities in LMICs do not have enough appropriately trained staff (including surgeons), proper equipment and supplies, or financial resources to quickly and adequately treat burn injuries. Meaning that, over time, horrific accidents can turn into chronic injuries and disfiguring disabilities, like the contracture Bibas suffered from. Patients are also often unable to make the long trip to medical centers where they will need months, or even years, of procedures to restore the necessary movement of joints.

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Dr. Tesfaye Mulate, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon working at the CURE Children's Hospital of Ethiopia treats hundreds of patients with severe burn injuries each year. The hospital averages around thirty burn contracture release procedures per month; in contrast, in high-income countries patients with burn injuries rarely need burn contracture release procedures because acute burn care as well as early splinting and physical therapy prevent severe burn contractures from occurring. Dr. Mulate notes, "Many of the burn injuries I treat are preventable and could have been avoided through simple measures such as elevating the cooking station at home or treated by ensuring access to simple first aid."

Approximately 11 million severe burn cases occur globally every year

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 80-90 percent of burns occur at home, where unsafe cooking environments and open flames put women and children at a greater risk of suffering severe burn injuries. In many households, women are responsible for food preparation and childcare, and infants and young children often crawl, play, walk (or even run) around open cooking fires.

The issue of cooking fuels and fires related to indoor household air pollution has rightly received much attention, as it sits at the intersection of many global health and development priorities, including gender equality, climate change, and public health in general. But the burn issues related to cooking fuels and fires also need to be spotlighted. Advocacy efforts have contributed to greater awareness of the dangers and the prevention of burn injuries in the home. However, despite advocacy and implementation support for prevention of severe burn cases, efforts to date have not focused on care for the millions of burn patients around the world who fall victim to injury and lack access to the medical treatments they need to overcome their injuries.

Every three seconds, someone around the world requires medical attention for burns and approximately 11 million severe burn cases occur globally, every year. Although severe burns happen in all countries, they are a significant cause of death, disability, and economic devastation, among the most vulnerable communities, LMICs, who often do not have access to safe and affordable, high-quality medical care. Because 95 percent of fire-related burn deaths occur in LMICs, burns have been called a disease of poverty. Other common sources of burn injuries in LMICs include electrical burn injuries (like the one Bibas suffered) as well as burns caused by acid and other chemicals.

Even though Bibas received life-changing care early on, he still returns to Kathmandu, seven years after his initial accident to further refine his bulky skin grafts, and he plans to complete his final surgery in 2023, after finishing his school exams—a task that would not have been possible without the initial burn contracture release. But for millions of patients around the world, treatment for burn injuries and resulting deformities is not an option. Five billion people around the world lack access to safe, affordable, and timely surgical care, which often includes burn management and contracture releases. Inequities in access to and availability of basic–but-necessary–emergency wound treatments often lead to avoidable lifelong deformities and deaths. No person should have to suffer a preventable and treatable disability because of their geography or income level.

Efforts made to improve access to care and to strengthen local health-care infrastructure and surgical systems provide an opportunity for individuals to break free from the cycle of disability and poverty caused by avoidable and untreated burn injuries. National and global health advocates, health-care providers, as well as governments and funding agencies should focus their attention not only on the prevention of burn injuries, but also on ensuring access to high-quality emergency care, including surgery when needed, and ongoing rehabilitation care.