This summer, Mexico has experienced extreme weather conditions resulting from two major heat waves. Those events included the country's hottest day ever, the warmest June since 1953, a heat dome that resulted in more than 100 deaths, more than 2,000 reported cases of heat stroke, and the massive die-off of endangered monkeys. Those scorching temperatures also brought threats to infrastructure, including the power grid.

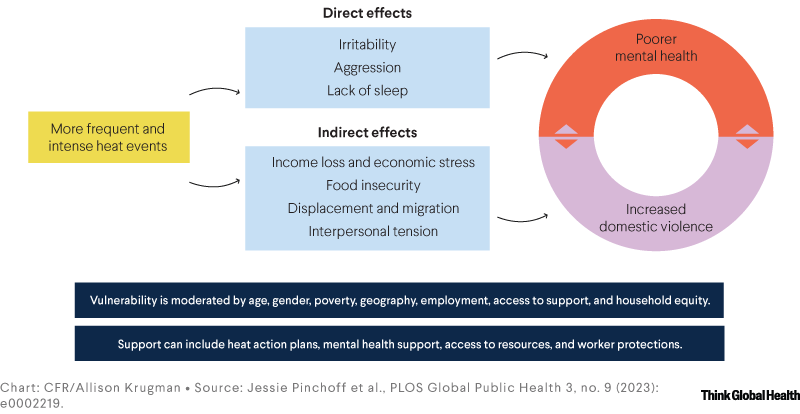

A growing body of research from around the world suggests another insidious harm from extreme heat: increases in conflict, intimate partner violence (IPV), and sexual and gender-based violence (GBV). Evidence is emerging that rising temperatures could be linked with increases in crime and intergroup violence. Exposure to extreme heat is also associated with irritability, challenges sleeping, depression, and anxiety.

To explore critical issues affecting young people in Mexico, our team conducted the first study to explore a relationship with domestic violence reporting among adolescents and young adults in the country.

The project began in 2021 as a web-based questionnaire focused on perceived harms related to COVID-19. The 2022 form included a new round, adding questions on climate change, mental health, and violence. This second round surveyed more than 150,000 adolescents and young people (ages 15 to 24) across Mexico. The analysis on climate and violence uses the second round as a cross-sectional survey because climate questions were new in this round.

Currently, no gender or climate policy addresses the links between climate events and risk of violence for women and girls. As Mexico faces more heat waves and increasing rates of GBV, research should be conducted to inform policies that address the intersection of extreme heat and domestic violence.

Climate and Youth

The world's 1.8 billion young people, the largest generation ever, will be exposed to more extreme climate events over their lifetime than any previous generation. Whereas a person born in 1960 will on average experience about four heat waves in their lifetime, someone born in 2020 could experience as many as 30 or more under current climate pledges. This projection has acute and chronic effects on social, emotional, physical, mental well-being, as well as on the intersecting crises of mental health and domestic violence.

The world's 1.8 billion young people will be exposed to more extreme climate events over their lifetime than any previous generation

Children and adolescents are at particular risk for long-lasting and incremental mental and emotional impacts of climate change because of their rapidly developing brains, vulnerability to disease, dependence on family, and limited capacity to avoid or adapt to threats. They experience long-term impacts from adverse childhood experiences, including domestic violence, that affect their future physical and mental health, educational attainment, and earning potential.

Exposure to different climate events including flooding, heat waves, drought, or hurricanes, and experience of a common mental health disorder (CMD) defined based on symptoms of depression or anxiety are found to be linked. Some 42% of young people who participated in the 2022 survey experienced a CMD, and exposure to any climate event increased this significantly.

Households in the lowest wealth tertile that had experienced a COVID-19 related economic harm were most likely to have also experienced a climate event, suggesting how the most vulnerable are doubly affected. More than a third (37%) of survey respondents reported that they had experienced at least one episode of violence in their lifetime, and more than a quarter (30% of girls and 26% of boys) reported a perceived increase since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The second round of the survey remained open from November 2021 to July 2022. During this time, Mexico was affected by heavy rains and flood events resulting from major hurricanes interacting with cold fronts. In March 2022, an anticyclonic circulation decreased the probability of rain over most of the country, leading to hot temperatures and repeated heat waves. Last year, published findings showed that about 1 in 10 youth recalled at least one major climate event in the last 12 months. Those who experienced such an event were much more likely to report a CMD, particularly during heat waves.

The physical and emotional development during adolescence has important implications for subsequent achievements and behaviors. Adolescence is filled with important life events, including graduating from school, entering the workforce, starting a family, and moving away from childhood homes. Adolescence is also when gender disparities emerge, shaping vulnerability to violence and mental illness. During these critical development stages, young people may be particularly vulnerable to the compounded risks of domestic violence, extreme heat exposure, and mental health. Structural inequities such as poverty or limited access to resources further exacerbate those challenges. Programmatic and policy barriers to violence prevention exist for mental health support.

How Heat Can Increase Domestic Violence

Rising temperatures can directly or indirectly trigger cycles of violence and poor mental health

Gendered Impacts

UN Women highlights the ways that climate change exacerbates the risks of violence against women and girls in particular. Research shows a link between heat waves and GBV. One study in Bangladesh finds increased rates of women and girls marrying, often early or forced, in the year following a heat wave. Another in Madrid, Spain, notes that the risk of femicides and IPV reported to police increased in the one to five days following a heat event.

In Mexico, levels of violence are generally quite high. The country has the nineteenth highest rate of intentional homicides as well as high rates of violence against women and children. Evidence from Mexican public hospital records shows that between 2020 and 2023, more than 62,000 adolescents (those 12 to 17 years old) who were admitted to hospitals had domestic violence recorded by medical or nursing staff on a case note. More than 90% of the injured adolescent patients were female. Recent studies in Mexico estimated that more than 70% of 50.5 million women and girls older than 15 have experienced some kind of violence in their lives, of whom 11% experienced violence in their households.

This study is one of the first to explore links with extreme heat in Mexico and the broader Latin America and the Caribbean region. Adolescent girls were slightly more likely to report a CMD and also slightly more likely to report violence (33% versus 27% of males reported at least one episode of violence in their lives). This figure was even higher for transgender and nonbinary people. Although reported domestic violence was only slightly higher for girls, the long-term impacts by gender are considerable, studies predicting exposure to domestic violence in childhood increasing IPV perpetration and victimization in the future. Globally, studies show that climate events such as heat waves increase day-to-day stressors that worsen mental health. The inability to cope with those stressors can compound with economic and food insecurity to lead to increased violence, often against women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities. Despite no evident major differences in reporting of violence by gender, research suggests the targets are more often women; for example, Mexico has one of the highest femicide rates in the world. Significantly, formal reporting for GBV is at best scarce, making it challenging but critical to quantify the prevalence and ensure that protective measures are put in place.

Building the Evidence for Effective Policy Action

Current research suggests that perceived exposure to heat waves in the last year is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing domestic violence among Mexican youth. This trend is supported by research from other settings. Yet adolescents and young people are often excluded from climate change research and policy. Although this is beginning to shift in the wake of growing youth-led movements and youth-centered participatory research approaches, effective policy should work across silos and consider how climate, mental health, and violence intersect and influence the lived experiences of young people.

Adolescents and young people are often excluded from climate change research and policy

One way to address this is through heat action plans, which are written documents intended to manage and coordinate key responses to reduce adverse health effects from extreme heat. Few exist, however, and none found mention violence. These plans include activities such as early warning systems, opening cooling centers, and ensuring access to drinking water to avoid dehydration.

New iterations that consider violence could, for example, build out policies and alerts to increase services, outreach, or awareness when early warning systems trigger a heat alert. Proactive policies such as creating urban green spaces have been shown to reduce violence, stress, and improve mental health. They also have a cooling effect, reducing temperatures nearby. Violence-specific support, including legal enforcement, specialized courts for domestic violence with trained personnel, access to emergency support services, and better integration into plans aimed at addressing extreme events could also be effective.

This study aims to generate new evidence on the relationships between heat and domestic violence to inform regional, context-specific heat action plans as well as intersectional age-sensitive and rights-based policies that address the health and well-being of young people in Mexico because climate change will only increase the frequency and severity of extreme heat events.