Last year was disastrous for climate, with global temperatures exceeding previous records every month from June to November in 2023. The cacophony of climate disaster notifications—air quality warnings, extreme heat advisories, flood, and wildfire evacuation orders—seemed endless. These extreme climate events reflect on a macro scale what Andrew Chang sees daily in his medical research and clinic.

Chang is a cardiologist and postdoctoral research fellow at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, studying the effects of environmental factors on heart health. For him, climate change is no longer a vague concept but instead an urgent problem that needs actionable solutions. "It's like the huge rock in Indiana Jones: It is already off the scaffolding. It is coming, and it is just gaining momentum," he says.

Increasingly, health-care professionals are confronted with the reality that climate and the environment are major determinants of health. To understand disease, they need to understand the environment. To care for patients, they also need to care for the environment.

Every single health professional needs to be brought up to date, needs to know how [climate change] affects their practice

Arianne Teherani

Medical education and training do not reflect this reality. For much of history, medical curriculum has focused on the individual body and the system within the four walls of a hospital. Environment had little role to play other than pollution and toxicology. This is changing thanks to a growing movement of health-care students and professionals calling for medical education to address the health threats created by climate change. In recent years, a slew of new educational initiatives, resources, and forums have been developed to better equip health professionals to confront these emerging threats.

"Every single health professional needs to be brought up to date, needs to know how [climate change] affects their practice, and needs to be prepared to prepare their patients," says Arianne Teherani, founding codirector of the University of California Center for Climate Health and Equity. The urgency of this task is conveyed by a 2009 Lancet commission report that called climate change "the biggest global health threat of the twenty-first century."

Facing a New Health Reality

Chang's first encounter with patient care in the context of climate change came in 2020.

He was just beginning his doctoral studies in epidemiology at Stanford when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out and a terrible wildfire season shrouded California in smoke for months. A new father at the time, Chang remembers gazing out at the orange sky wondering what kind of world his son would grow up in. "It looked like Blade Runner outside," he recalls.

Meanwhile, in the cardiology clinic where Chang worked, patients brought in questions about how the smoke affects their health. He remembers patients asking, "What should I do?" and feeling unprepared to respond. He had spent almost a decade learning the complex physiology of the heart, but no one had ever taught him how to advise patients during wildfire season or other extreme climate events. It struck him that climate change and environmental factors were entirely absent from his medical school curriculum.

Natalie Baker, a student at Harvard Medical School who grew up in northern California, had a similar realization during the 2020 wildfire season. Motivated to change what she saw as a dearth of planetary health in her medical education, she joined a student group called Students for Environmental Awareness in Medicine and worked with faculty to develop a new environment and health curricular theme.

Their new curricular theme launched this past summer. It weaves planetary health modules into the existing preclinical courses in which medical students learn about the different organ systems. When students learn about diseases affecting the lungs, such as asthma, they now also discuss environmental exposures that might exacerbate those diseases.

Climate change will dramatically alter both the landscape we're practicing medicine in and our careers going forward

Anna Lachenauer

"Climate change will dramatically alter both the landscape we're practicing medicine in and our careers going forward," says Anna Lachenauer, a medical student at Stanford Medical School involved in similar curricular reform efforts. "We're hopeful that by starting to talk about these issues in medical school, we can better train future physicians to address them."

Climate Enters the Health Curriculum

Baker, Chang, and Lachenauer are part of a generation of health-care students, educators, and professionals mobilizing to remedy the lack of training on how to care for patients on a planet shaped by climate change.

In recent years, health professional schools countrywide have made strides toward incorporating planetary health into their curriculum. These reform initiatives are often student led and focus on the early preclinical years. According to a 2022 survey by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), 55% of U.S. medical schools reported including the health effects of climate change as a topic in required courses, more than double that reported in 2019.

As health professional schools tailor these new educational initiatives to suit their program structures, they also collaborate to develop shared tools, resources, and forums. One such tool is the Planetary Health Report Card, which tracks and evaluates the planetary health curriculum at health professional schools. Founded in 2019 by U.S. medical students, the tool is now used by health professional schools worldwide, from South Africa to New Zealand, to gain and sustain institutional support for curricular reform. Another collaborative resource is Climate Resources for Health Education, an expert-reviewed repository of lesson plans and materials about environment and health topics that was developed in a joint effort by Columbia, the University of California San Francisco, Emory, and other U.S. medical schools.

Medical students involved in these efforts have also created their own forum, Medical Students for a Sustainable Future. The organization seeks to prevent and address the health harms of climate change through curricular reform, advocacy, research, and resource sharing. "I envision this organization as an umbrella to unite medical students working on these efforts nationwide," says Baker, the incoming chair of the organization.

Although health professional schools have made progress integrating these topics into their preclinical curriculum, the task becomes more difficult as students enter clinical training, when they are dispersed across the hospital system with more direct patient care responsibilities.

A new resource that aims to tackle this challenge is Medicine for a Changing Planet, a series of 11 clinical case studies developed by the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health and the University of Washington (UW). The cases are designed to be directly applicable to clinical competencies and focus on a range of environmental challenges, from air pollution to vector-borne diseases to refugee health. "We are the ones who actually see the immediate effects of these things [emerging pathogens, toxins, environmental disasters] on health," says Peter Rabinowitz, director of the UW Center for One Health Research and a colead of the project.

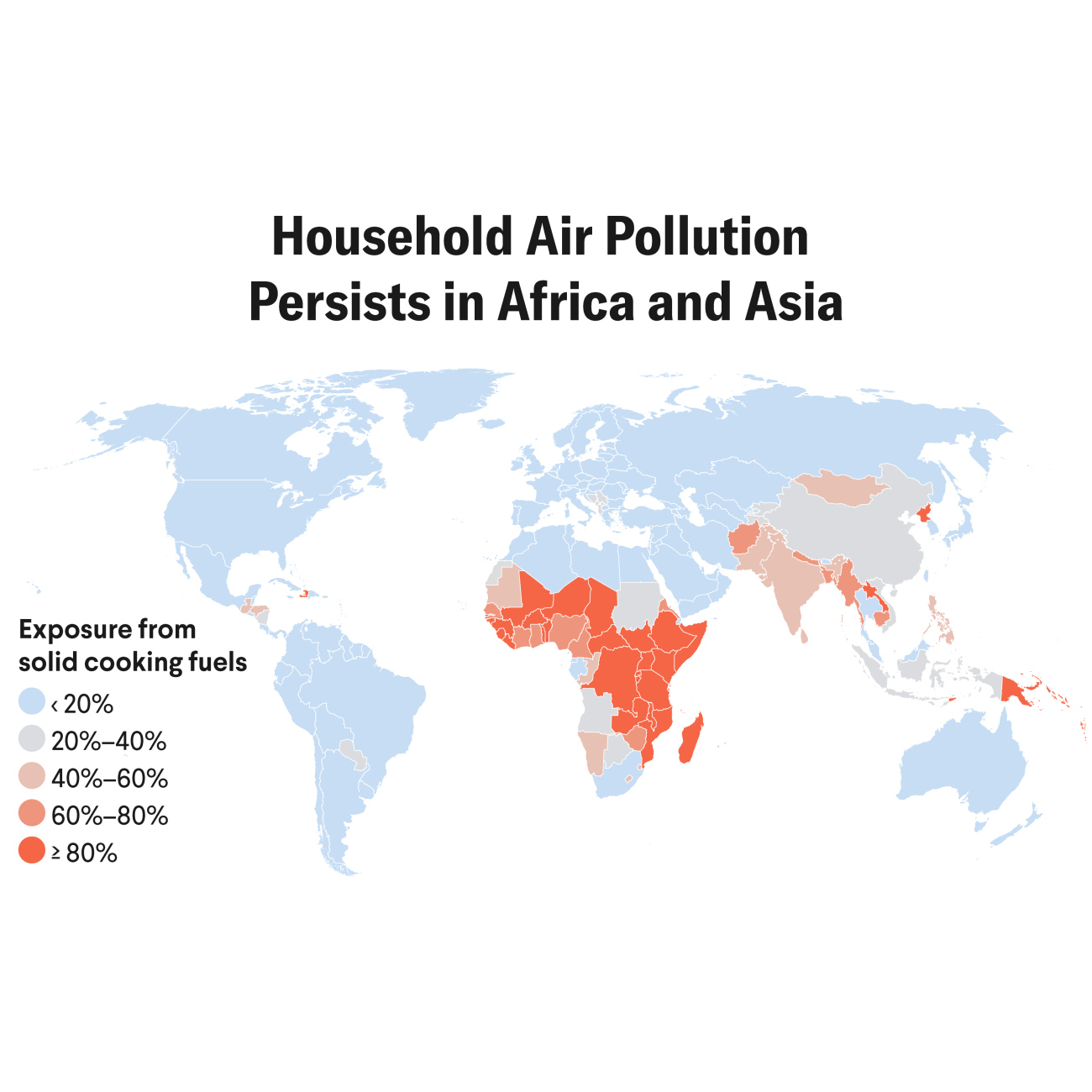

The clinical scenarios were developed in consultation with a diverse team of health-care professionals from around the globe, some at the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda. Approximately half of the cases are set in low-resource countries. Michele Barry, director of the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health and the other colead of the project, says that it is important to locate many of the cases in global, low-resource settings because that is where the impacts of climate change on health are most pronounced.

"More than 80% of our emissions are coming from high-income settings, but the most vulnerable populations are feeling their impact in low [income] countries," explains Barry. She believes the cases are a valuable educational resource for medical students and other health professionals across all disciplines and levels of training.

We are the ones who actually see the immediate effects of these things [emerging pathogens, toxins, environmental disasters] on health

Peter Rabinowitz

Jay Lemery, director of the Climate and Health Program at the University of Colorado, also emphasizes the need for health professionals at all levels, including the senior level, to continue learning about the impact of climate change on health. Lemery has worked tirelessly to develop continuing education programs for physicians who are seeking to further their practice by engaging in climate and health work.

One such program is the University of Colorado Climate & Health Science Policy Fellowship, which enables practicing physicians to pursue work in climate and health education, research, and policy. Fellows meet weekly for didactics, attend national and international conferences, and complete two policy preceptorships where they are paired with a federal agency and a nonprofit working in climate and health.

Another unique continuing education program based at the University of Colorado is the Diploma in Climate Medicine, which allows physicians to earn a nonmatriculated diploma for completing five one-week certificate programs. Lemery says that this option is intended for practicing health professionals who want to become leaders in this field but do not have the time to complete a year-long fellowship.

The educational tools, resources, and initiatives mentioned are examples of progress, but Lemery says that much work remains to be done. Many health professional schools in the United States still lack a climate curriculum, and funding and training opportunities in climate medicine remain scarce for senior health-care professionals.

"This is an all hands on deck crisis. We need [health professionals] from every background diving into this," Lemery says.