If COVID-19 is the crucible, then politics is the forge. If novel coronavirus is mortar in which humankind finds itself, politics is the pestle. If the outbreak in Wuhan, quickly spreading to the rest of the world, was the trigger, then politics was the finger on it—pulling over and over and over again.

Politics is exacerbating a public health issue, making the virus much more deadly than what it should be

In a period of public health crisis, scholars and policy makers are often quick to ask the following question: what has the new public health threat revealed about a government's health care system and its ability to respond in a timely and effective manner? Do governments have the infrastructure, resources, and technology needed to curtail the spread of disease? While focusing on health systems is important, this can often lead us to overlook what viruses reveal about the role, nature, and consequences of a country's political environment. In a time of the coronavirus in the United States, politics is exacerbating a public health issue, making the virus much more deadly than what it should be.

Politics, in other words, can literally kill us.

Therefore, perhaps a more important question we should ask is the following: What have we learned about politics and the coronavirus in the United States? When can politics help, and when can it hurt our response? And what positive lessons can we learn going forward?

When can politics help, and when can it hurt our response?

The coronavirus reveals both the good and bad of U.S. politics: partisan division has marginalized certain segments of the population, contributing to a potentially worse health outcome for immigrant and minority groups. Additionally, ongoing division along republican and democratic party lines made it nearly impossible to achieve a swift compromise on key policy issues, in turn delaying the federal government's response. Add to this the politics of federalism and the sharing of responsibility between federal, state, and local responders, further hampering state-level responses in a period of crisis and despair.

The Politics of Marginalization

Politics is ultimately about the allocation of people and resources, making decisions about where to invest, and where not to, to the end of creating better societies. In democratic societies the power to allocate resources is held by those who are elected to governments, which reflects, in some ways, the will of the majority or a plurality of people in the population. This leads, perhaps naturally, to an inclination to privilege resources to help those in power, representing hence the majority of the population. While there is ample reason to respect this approach because on some level political decisions that reflect the majority perspective ultimately respect the fundamental tenets of a democratic society, there is also reason to scrutinize this winner-take-all approach. Abiding exclusively by the will of the majority also, by definition, sets aside the needs and aspirations of minority groups who did not succeed in electing a government that reflects their vision for the country.

In a time of crisis, the presence of marginalized groups who have been systematically excluded challenges our ability to respond

The politics of exclusion, rather than inclusion (which responds to the needs of all), has colored American life for the past several years. President Donald J. Trump was elected on a platform that was designed to be exclusionary, stoking political success in a furnace fueled with explicit targeting of immigrants, and implicit criticism of minority groups in general. Whether this was a successful strategy for President Trump in general is debatable. In a time of national crisis, it becomes abundantly clear that this strategy is dangerous. Creating groups who are marginalized and excluded during normal times fractures social cohesion and limits our ability to move forward collectively. In a time of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, the presence of marginalized groups who have been systematically excluded challenges our ability to respond in three ways.

First, groups that are accustomed to being marginalized are much less likely to trust government decisions or actions, making it harder for governments to bring about rapid collective action that can address national crises. In the context of coronavirus, when national appeals to physical distancing rely on general group adherence to national recommendations, this becomes a matter of national security, threatened by the politics of marginalization.

Second, and practically, the existence of groups that are marginalized and disconnected from the larger population creates reservoirs of disease if people in these groups are not treated. That will undermine efforts to address the pandemic on a population level, which depends on entire groups behaving cohesively. We have previously seen examples of this in cases where groups of new immigrants are under-vaccinated, leading to outbreaks of diseases like measles. In the context of coronavirus, a politics of exclusion leads to the likelihood of dramatic and poor outcomes as a direct result of these groups not being part of the greater whole.

A politics of exclusion, threatening the health of the entire population, reaping consequences from divisive policies

Third, excluded groups will almost inevitably have an unpredictable interaction with established health care and social service systems, likely avoiding them as long as possible but then potentially using them en masse when fear or disease spreads. This can represent an extraordinary challenge in the face of a pandemic where the greatest threat to health systems is a rise in number of cases requiring more hospital beds, for example, than are available. All of this points to the harms incurred by a politics of exclusion, threatening the health of the entire population, reaping consequences from divisive policies before the crisis.

The Consequence of Political Division

But bipartisan politics and division has also mattered. The coronavirus could not have emerged at a worse time than it did, amid a heated presidential election built upon months of vitriol, accusations, and competitiveness between the incumbent republican President Trump and democratic candidates. In this context, President Trump's initial reaction to coronavirus was painted with political accusations that the democrats were using coronavirus to undermine his administration, that this was the Democrats' new hoax, causing panic, frenzy, and disturbed markets. While the president emphasized that the coronavirus was under control, aided by his swift travel ban and containment measures, and publicly downplayed the virus' threat to the common flu, others within the administration as well as many democrats in congress and in the states openly sided with the scientists in emphasizing the importance of widespread diagnostic testing, social distancing, and resources to the states.

The coronavirus could not have emerged at a worse time than it did—in a heated election built upon months of vitriol, accusations, and competitiveness

With families suffering in this context, policy responses aimed at providing immediate relief were delayed due to these conflicting bipartisan viewpoints. By mid-March, the Democrats introduced a bill, Families First Coronavirus Response Act. This bill provided financial relief, mainly in the form of paid sick days (up to ten for full-time workers, prorated for part-time workers) to families that lost income due to closed businesses, food for families reliant on school-meal programs, and an expansion of SNAP (food stamp) benefits for jobless workers. Several congressional republican leaders, such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, referred to it as an "ideological wish," leading to a needless "thicket of new bureaucracy." This led to ongoing haggling between Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and President Trump, eventually leading to an agreement after a week of conflict and delay.

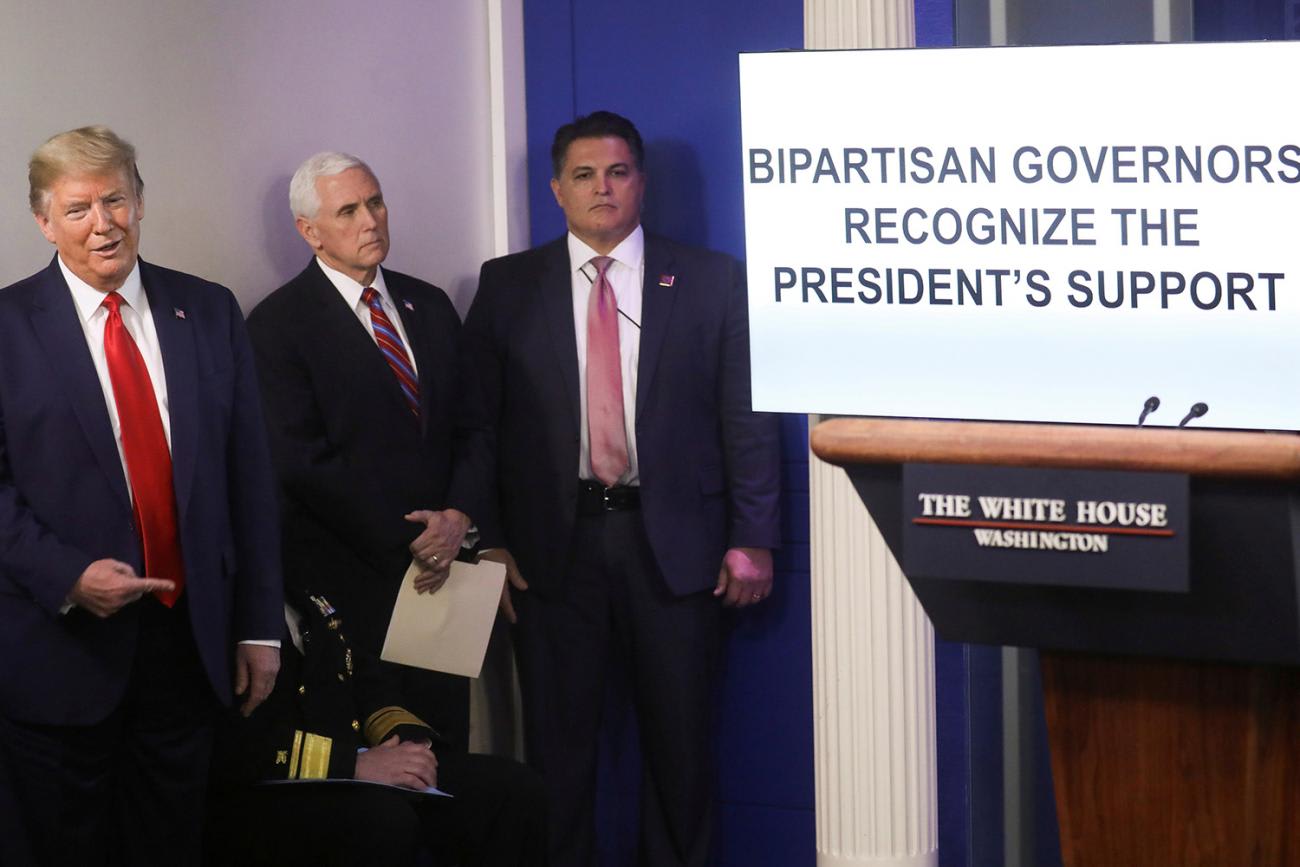

Political federalism has also been problematic. Trump initially disagreed with the governors over the broader urgency of the coronavirus. While democratic New York Governor Andrew Cuomo emphasized that the federal government needs to provide an equal amount of infrastructural assistance to the states, Trump vehemently rejected the idea by claiming that the situation was not as urgent across all of the states. What's more, there have been conflicting views over policy responsibility, with Trump blaming the governors for not stockpiling their own ventilators in time, claiming that they have no grounds to complain and wait on him for assistance.

When What Doesn't Make You Stronger May Kill You

In many ways, crises do not tell us anything new—they reveal what was true to begin with. In this global pandemic, what is revealed is a political system characterized by the politics of marginalization and bitter partisan divisions, at the expense of achieving what should be the goal of politics—creating a better society. While the country has moved along despite these political limitations through these times of coronavirus, this political dysfunction, quite literally, can kill us. How do we fix this? How do we fix our politics so that they serve us well, not poorly, in a time of public health crisis?

We suggest three solutions. First, we cannot allow a powerful majority and their interests to marginalize the few.

Health ultimately has to be seen as a common good, supported by our collective investment, for the benefit of all

Politicians need to focus on marginalized groups and ensure they receive necessary support. Support for the few has become a partisan issue, with Democrats casting themselves as the party of the marginalized and Republicans, almost in reaction, resolutely avoiding any efforts that seems to pay attention to these groups. But this pandemic makes it abundantly clear that the problems of the few quickly become the problems of the many. A marginalized group can become a viral reservoir threatening the health of all. Health ultimately has to be seen as a common good, supported by our collective investment, for the benefit of all.

Second, we cannot let partisan divisions and elections keep us from following the science and providing the truth. Science should not be red or blue—or even a purple mix of the two, to paraphrase former President Barack Obama. It needs to be a neutral grey. Several opinion polls have shown extraordinary partisan divides in how the science around this pandemic has been perceived. Identifying how we can elevate the science to transcend these divisions seems to be a central challenge in the coming years.

Third, we should not let political federalism get in the way. Now is not the time for the president to blame the governors for their lack of resources and initiatives. In a time of crisis, presidents need to set their political differences aside and show leadership immediately by providing assistance to all of the states.

Bipartisan support for rational actions informed by science can be achieved—and it is happening. But we cannot rely on crisis and fear to mend our political differences and find policy solutions. Solutions to the next crisis have to be sown in times when we do not have a crisis on our hands. Investing in public health infrastructure and in the science that will guide us during the next crisis should be bipartisan issues of utmost urgency. Whether we can get there or not may ultimately determine whether politics kills more of us than the coronavirus will.