During a study in Zambia that surveyed people with disabilities who are also HIV positive, one of the participants recalled the stigma and discrimination they faced from health-care workers when they sought medical care. They remembered telling a physician, "Doctor, I'm human…a lot of disabled people come to the hospitals. You discourage us…that's not how it’s supposed to be."

This experience is common for people with disabilities. Of the estimated one billion people with disabilities globally, many lack access to appropriate health care, as well as health information specific to their condition. This is especially true in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 80 percent of people with disabilities live, and where women and children with disabilities have fewer resources. Humanitarian crises also quickly reveal how people with disabilities are left behind because they are at greater risk of harm and their needs are often overlooked or excluded from the delivery of aid.

People with disabilities make up more than 15 percent of the world's population

In the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the United Nations defines persons with disabilities as people "who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others." As people with disabilities make up more than 15 percent of the world's population, achieving the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and Universal Health Coverage (UHC) are impossible without their inclusion.

Information Deficit

Stigmatization, poverty, social exclusion, and challenges reaching health-care facilities are among the reasons people with disabilities lack access to care. There is also growing recognition that a lack of information is a barrier. Many people with disabilities are not aware of their right to health care, where they can access care, and which services are available to support their specific medical needs because information on these is not readily available. This prevents them from seeking specialized surgical treatment, medications, counseling, rehabilitative care related to their disabilities, and accessing assistive devices or other forms of treatment that could improve the quality of their lives.

Health Provider Knowledge and Data Gaps

A knowledgeable health-care workforce is critical to delivering good care to people with disabilities, but there is limited data available to health providers about disabilities, including details about the prevalence, incidence, causes, and treatments for different conditions.

What's more, some health care providers are influenced by harmful beliefs about people with disabilities. These include beliefs that people with disabilities are cursed or possessed by demons and that they can only be healed through religious and traditional practices such as prayer, fasting, chants, and exorcisms. Such beliefs are often promoted by influential community leaders. They persist in many places around the world and lead to discrimination, marginalization, and societal exclusion.

Globally, people with disabilities are underrepresented in most national censuses, including in the United States. According to The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "A 2021 report by the National Disability Rights Network describes a pattern of historically low decennial census participation rates for people with disabilities, and the Census Bureau considers the disability community to be a hard-to-count population at great risk of being undercounted and misrepresented."

This lack of data surrounding disability hinders the ability to create policies and funding mechanisms that improve access to care, and that protect and promote the rights of people living with disabilities.

More than a decade ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank collaborated on the World Report on Disability 2011, a landmark report that covered a range of topics related to disability, including access to health care. A 2019 report by WHO and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine researchers was published on this topic and the Missing Billion initiative began the following year. The report focused specifically on access to health care and highlighted important data on health disparities for people with disabilities. For example, children with disabilities are two to three times more likely to be malnourished, and two times more likely to die of malnutrition than children without disabilities. Women with disabilities are 1.5 to two times more likely to have preterm births or give birth to low-weight babies than women without disabilities. Adults with disabilities have an HIV prevalence rate that is two times higher those those without disabilities, and the diabetes prevalence rate among people with diabetes is two to three times higher than it is in adults without disabilities. Additionally, people with disabilities are four times more likely to have poor mental health status than people who do not have disabilities. And they are 50 percent more likely to suffer from catastrophic health expenditures compared to people without disabilities.

At the 74th World Health Assembly in May 2021, a resolution was passed that called for better access to health care for people with disabilities so they may achieve "the highest attainable standard of health," as prescribed by the CRPD. The resolution specifically mentions the importance of "accessible health-related information" and calls for a report to focus on the issue of health equity for people with disabilities.

This year saw the second-ever Global Disability Summit (GDS), held in Norway in February, as well as a pre-summit event that took place in January. The events focused on disability inclusion in the health sector. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, participated in both events and at the pre-summit, he commented on the right to health care for people with disabilities and the "barriers that prevent people with disabilities from realizing this right" including the accessibility of health information. The summit included a panel of disability rights activists and advocates who shared their own experiences as people living with disabilities and their interactions with the health-care system. The need to access health information was a common theme.

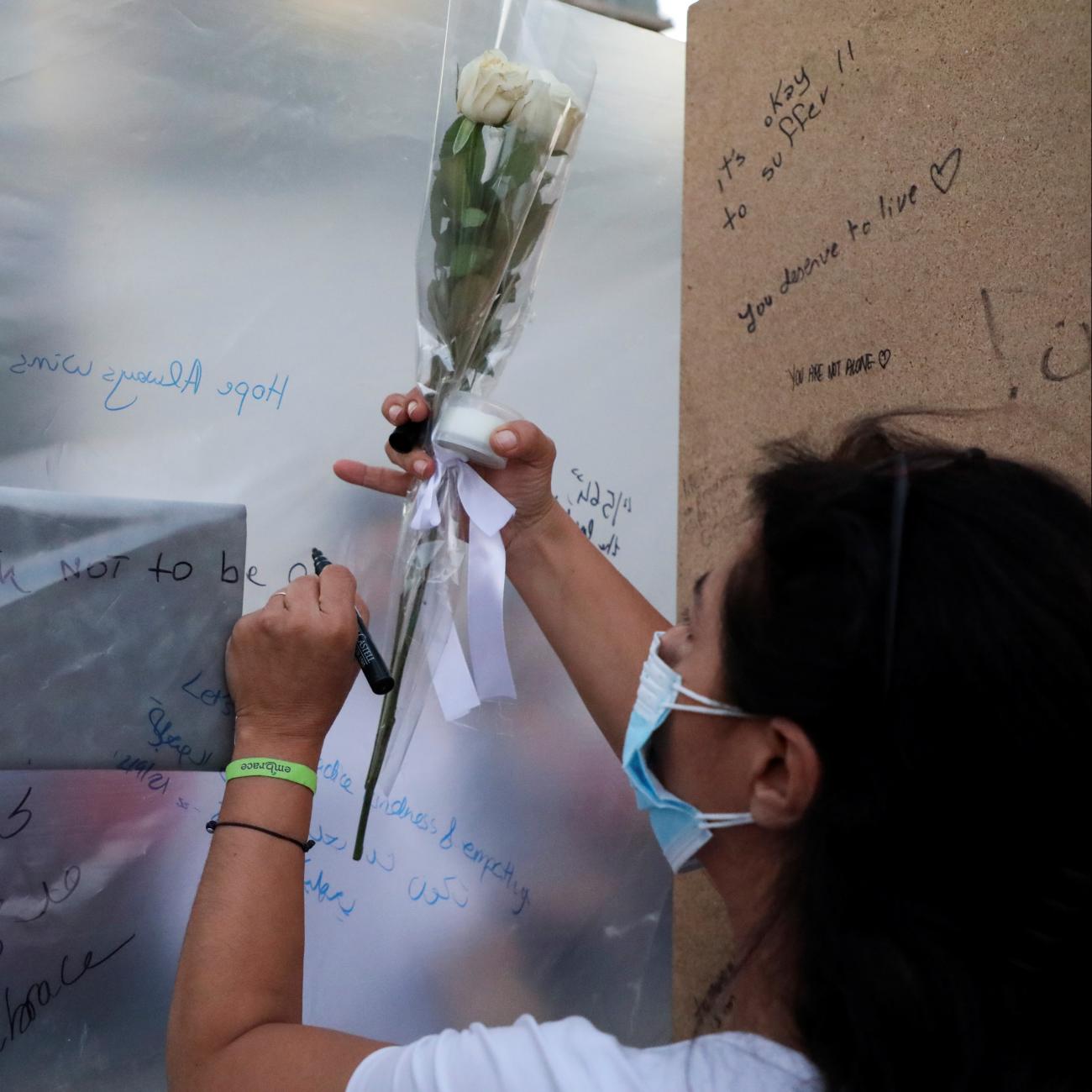

People with disabilities are four times more likely to have poor mental health status than those without disabilities

"Information is power," said Ashura Michael, an International Disability Alliance (IDA) - UNICEF Youth Fellow from Kenya, who stressed that unless people with disabilities are given access to health information, they will not receive the quality of care they need.

Olive Namutebi also participated in the panel. She is the executive director of Albinism Umbrella, an organization that works alongside various stakeholders to advocate and lobby for an enabling environment where persons with albinism can thrive. Namutebi said, Inclusivity "comes with knowledge, and we always say knowledge is power."

Namutebi said because her albinism is visible, health-care workers often assume that she is seeking care for her skin condition, even when she is seeking treatment for another illness. The often mistaken assumptions made by health-care workers highlight the fact that there is a deficit of information and training for health-care workers about the unique health needs of people with disabilities.

Christopher Agbega, from the Ghana Non Communicable Disease Alliance, added that when it comes to information, one of the best ways to make sure that people get the right information is to have a "people-centered approach" and include people with disabilities in the process of service delivery.

Michel Landry, chair of Physical Therapy and associate dean of Global Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, noted in a 2021 article for Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University that "sustainable solutions in this field must be made as a team, with people with disabilities at the center and in control of the process."

For health-care providers, standard procedure and best practice is to always listen to patients. However, that is not the experience of many people with disabilities when they interact with health-care systems. They are frequently ignored or dismissed, and sometimes even face outright hostility from health-care workers. Whether this behavior stems from ignorance, or from negative beliefs about disability, it has serious consequences for people with disabilities and ultimately contributes directly to a lack of access to care for people with disabilities.

The increased interest in access to care for people with disabilities and health information in the health sector comes at a critical time. From Ukraine to Ethiopia, Yemen and beyond, humanitarian crises are affecting people with disabilities disproportionately. Their ability to receive essential health services has been more restricted. The COVID-19 pandemic has also affected care and has been a catalyst for more in-depth analysis on access to care for people with disabilities and the health disparities they are experiencing.

In Malawi, a project is underway that is bringing together a number of stakeholders, including the NGOs CURE International and Kupenda for the Children, as well as the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Malawi. The project is improving the provision of care to patients with surgically treatable disabilities, while also raising awareness about disability rights and helping to ensure that people with disabilities and their families are informed and knowledgeable about their rights and their different treatment options. This project is also helping to advocate for people with disabilities and their rights among the general population and key community stakeholders, including pastors and other religious leaders, community leaders, and health-care workers. While limited in scope, the project suggests a way forward.

People with disabilities should be involved in their own health decision-making and in the development of programs that are meant to serve them. In seeking to provide care to people with disabilities, health-care practitioners should strive for a posture of inclusion and adhere to the principles that guide the disability rights movement, including the idea of "Nothing about us without us."