Both the United States and China were quick to congratulate themselves after their recent summit at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting. After years of deteriorating bilateral relations, the countries agreed to resume military-to-military communications and accelerate climate actions and made progress on efforts to curb Chinese fentanyl exports, reduce risks associated with artificial intelligence, and expand people-to-people exchanges. President Biden described it as “some of the most constructive and productive discussions we’ve had.” China labeled the talks as “strategic, historic and directional.”

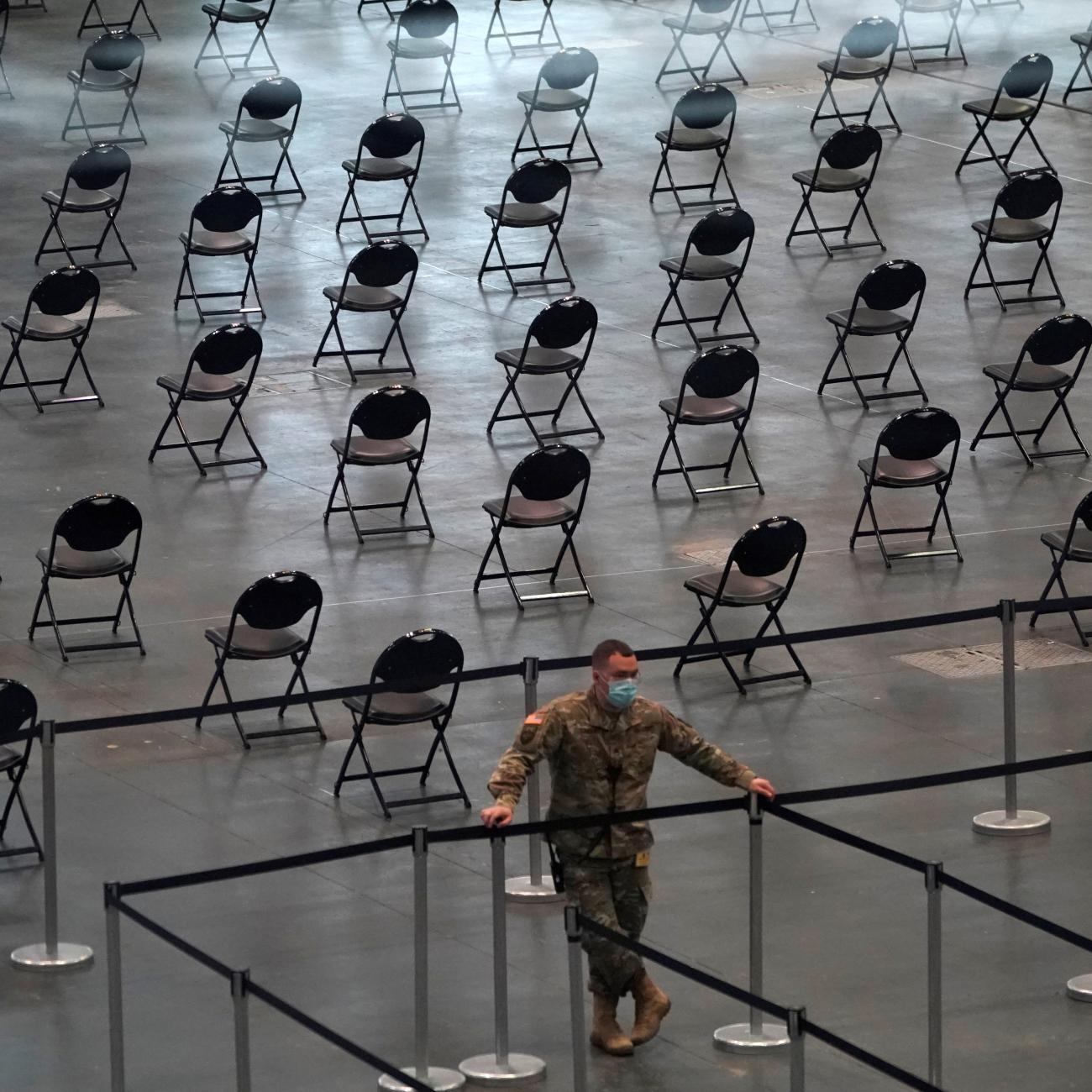

Missing from the areas of strengthened cooperation, however, was anything having to do with pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. The countries agreed to initiate working-group consultations in ten areas but improving cooperation against pandemic threats was not among them, despite the devastating impact that COVID-19 had on the economies and societies of both countries. The summit’s failure to advance such cooperation is worrying and should prompt discussion of how the United States and China could work together to strengthen collective health security.

COVID-19 killed at least 1.4 million people in China

The Importance of U.S.-Chinese Cooperation on Pandemic Threats

As Rebecca Katz and I argued in a recent Council on Foreign Relations special report, the COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity for the United States and China to prepare for the next pandemic. It’s happened before. After the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome crisis in 2003, the United States entered into a multiyear partnership with China’s Ministry of Health to develop more robust public health capabilities, infrastructure, and bilateral collaboration to defend against major disease outbreaks.

U.S.-Chinese cooperation on pandemic threats diminished after 2018 following China’s move to withhold H7N9 avian flu strain samples from U.S. researchers. This cooperation then broke down with the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, further exacerbated by the politicization of the pandemic response.

That breakdown contributed to the damage that COVID-19 inflicted on China, where it killed at least 1.4 million people and has been a major factor in halting China’s economic miracle, and on the United States, where it killed 1.1 million people and will have cost approximately $14 trillion by the end of 2023.

Those catastrophic impacts, however, have not persuaded the countries to take collective action against pandemic threats. Amid warnings that another coronavirus outbreak is “highly likely,” China and the United States remain as or more vulnerable to dangerous disease events than they were before COVID-19. This is underscored by the World Health Organization's recent expression of concern regarding the spike in respiratory illnesses among children in northern China.

In our report, Katz and I argue that strengthening global health governance against pandemic threats demands that the United States and China rekindle cooperation. Doing so will require moving past geopolitical tensions that have prevented the two countries from collaborating during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most fundamentally, the United States and China should acknowledge that geopolitical competition should not dictate whether and how the two sides collaborate in addressing pandemics as a transnational threat. They should renew cooperation on basic public health activities such as monitoring for emerging infectious diseases, sharing samples and genetic sequences of new pathogens, and exchanging epidemiological and clinical information. Achieving such a global health détente could create more political space for health diplomacy in multilateral frameworks such as the G20 and could foster conversations that bring together a mix of government officials—who participate in an unofficial capacity—and nongovernmental experts, all sitting around the same table as part of the Track 1.5 dialogue.

Both sides lacked the political will to use the summit to address health security through a working group or other mechanism

The Problem of Political Will

The Biden-Xi summit demonstrated that the U.S. and Chinese governments can agree to improve bilateral relations on issues of shared concern. Clearly, both sides lacked the political will to use the summit to address health security through a working group or other mechanism.

Reestablishing bilateral cooperation on pandemics would require both governments to identify a lead agency and ensure other stakeholders with technical expertise were involved in the consultations. But such bureaucratic considerations are not the central impediment. Neither President Biden nor President Xi appears interested in forging bilateral collaboration on health security.

In the United States, the link between COVID-19 and China remains highly politicized, and the Biden administration appears to prefer to address health security issues through partnerships with other countries it views as more like-minded. Although important, those partnerships are not enough for tackling the pandemic threat. On the Chinese side, having staked his political stature on what turned out to be a disastrous COVID-19 response, President Xi now seems inclined to distance himself from the issue of pandemic preparedness. In addition, discussions on health security with the United States would require more transparency and information sharing—openness that is contrary to the secretive nature of the increasingly autocratic regime.

Unfortunately, those domestic political calculations have become excuses for inaction. Pandemics connect American and Chinese health in ways that geopolitical rivalry cannot manage. In their diplomatic rhetoric, the countries plainly identify the shared nature of the pandemic threat; for example, the U.S. Secretary of State recently said, “there is only one way to enhance global health security: together.” At some point, that truism needs to become the basis for diplomatic action. Like it or not, American and Chinese health security requires collaboration.