COVID-19 should be global health's big moment: if there were ever a time for data and expertise to take the lead and inform official action, this pandemic is it. So why has leadership in the worst pandemic in a century been left to politicians and corporations?

To our mounting horror, though, it's clear that technocratic knowledge has no sway without political will

One of the core convictions of people in our field is that evidence can and should inform policymaking to a meaningful degree. This pandemic calls that into question. There is no shortage of expert analyses and recommendations—what we haven't seen is actual demand for them. Early on, the primary global health focus was on advising the United States and other national governments. To our mounting horror, though, it's clear that technocratic knowledge has no sway without political will. The challenge is to drive change in a world uninterested in expert opinion. This can be done by appealing directly to the public, targeting global organizations that still appear to value science, or focusing on state and local government which may be more amenable to targeted advocacy efforts. All of these approaches have their weaknesses.

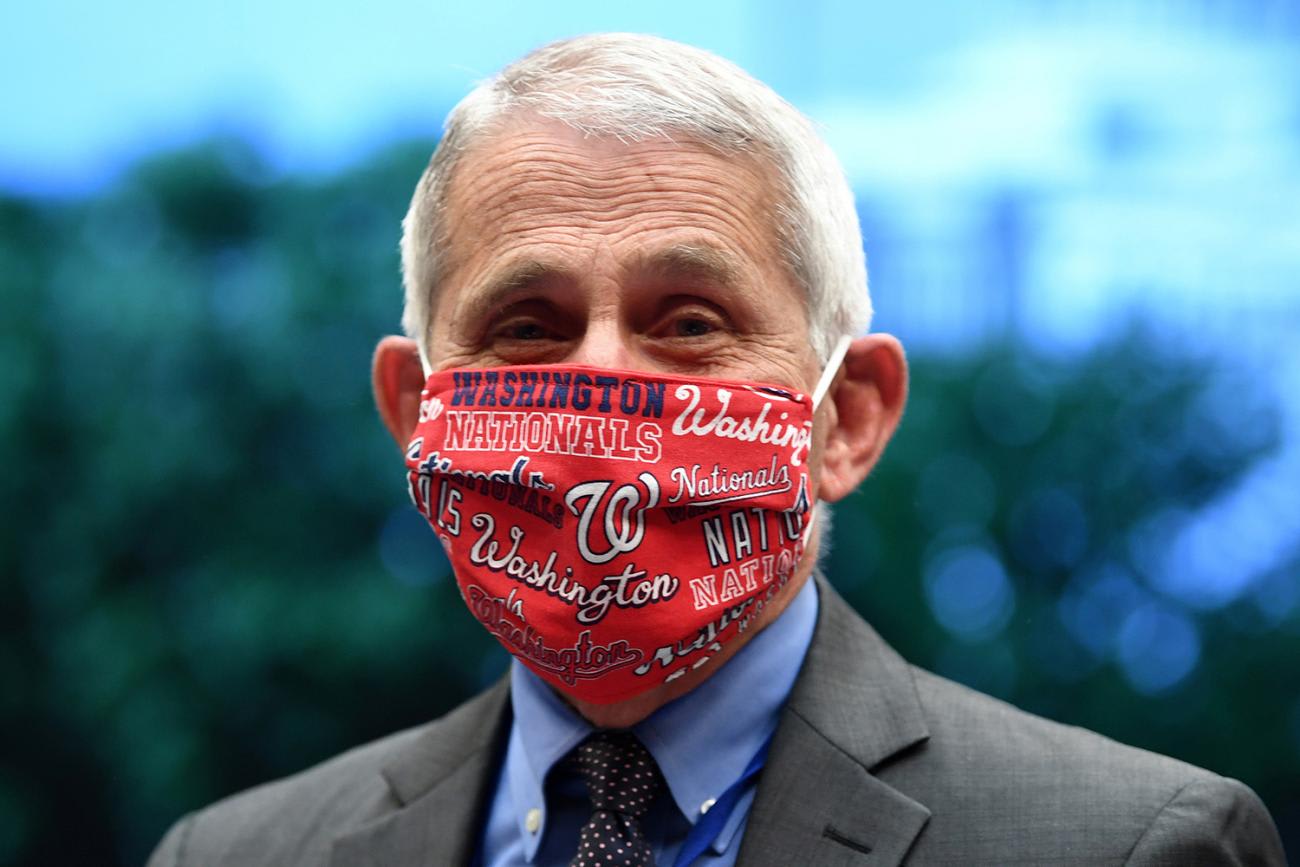

One approach is to go directly to the public. Public health messaging around how individuals can minimize the risk to themselves and others can drive both personal behavior and advocacy for policy change. One of us (A.S.) gave a TED Talk in early March using that approach that was seen approximately twenty million times. However, there is limited precedent for such communications under so much scientific uncertainty, with expert consensus still shifting beneath our feet.

Expert consensus still shifting beneath our feet

That TED Talk is now largely out of date. The advice on masks has been invalidated by the frequency of COVID-19 transmission by individuals who are not showing symptoms at the time. And while most cases are "mild," even those increasingly seem to carry potential long-term consequences. Indeed, guidelines on travel and gatherings had already tightened by the time the video was posted online. Most people are not used to seeing the research process evolve and do not expect recommendations to change in real time. The reversal on wearing masks, for example, has actively angered many and come at a wider cost to our field's credibility.

On the other end of the audience spectrum, many experts have advised multilateral organizations and partnerships like WHO, Gavi or the Global Fund that have explicit commitments to identifying and implementing technical input. Surely this approach should be high-impact?

Surely this approach should be high-impact?

Yet a recent open letter from scientists concerned about messaging on aerosol transmission highlights the outsized role of institutional politics in shaping official guidance. The withdrawal of the United States from WHO may now further decrease the scope for influence by many of these researchers. Meanwhile, in the case of an Advance Market Commitment for countries to pre-commit to purchasing COVID-19 vaccines when successful candidates become available, Gavi's draft technical proposal and related investment case builds closely off of earlier pilots for pneumococcal disease and Ebola without directly engaging more recent analyses from the same academic economists and think tanks who had originally developed the idea but see important distinctions that require adaptation to the pandemic context.

Conversely, focusing on the subnational level seems to have had greater traction within the United States, but within an inherently constrained fiscal space. Advisors including former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) directors, leaders of international NGOs like Partners in Health, and faculty at university research centers who have collaborated with state governors to set up testing and contact tracing programs in tandem with (or as the solution for) economic lockdowns. Unfortunately, the absence of federal funds limits their ability to scale up—as has the waning of public support.

Local policymakers seem most open to receiving and implementing guidance but appear to be least prepared for managing the economic fallout

Finally, local policymakers seem most open to receiving and implementing guidance but appear to be least prepared for managing the economic fallout, as declining tax revenues means slashing services rather than increasing them. This is where we have devoted our own time—especially as private medical systems are often otherwise regarded as de facto sources of public health expertise despite their institutional conflicts of interest. We're aware of a few larger-scale capacity-building efforts, such as Bloomberg Philanthropies or covid-local.org, but many of those resources are geared toward the largest cities rather than the smaller metros and fragmented suburban regions that currently face the steepest rise in COVID-19 cases, which is all too likely to be followed by a wave of bankruptcies.

As a field, then, we must redouble our attention to building resilient health systems at all levels—and recognize the hubris of past "pandemic preparedness" scenarios or indices. As Vietnam's success has shown, novel medical technologies are not a prerequisite for infectious disease containment. And as the U.S. failure has shown, they are useless in the absence of delivery incentives.

One of our most important roles may be simply to prepare people for how bad the problem could become

Looking ahead, we should perhaps conceive of pandemic preparedness as a function of domestic governance structures and corresponding economic incentives. This becomes part of the project of decolonizing global health, and it entails both valuing deep local knowledge and rejecting national income as the central determinant of epidemiological models or policy prescriptions. A decolonized approach to preparedness also ensures that health response continues even when international travel comes to a halt. Against that backdrop, we must hold more space for policy pessimism. We need to hedge against ongoing scientific uncertainty and map out worst case scenarios, even when doing so doesn't readily point to evidence-based, innovative or scalable solutions. When it comes to reducing the risks of long-term morbidity, one of our most important roles may be simply to prepare people for how bad the problem could become.

Ultimately, though, global health depends on rebuilding public confidence in the value of our field—or perhaps earning that trust to begin with. On a basic level, that means partnering with our education colleagues to improve not just health awareness but also basic science literacy worldwide so that whenever we do have a vaccine people are comfortable taking it.

Yelling futilely from the sidelines, just when it matters most

Finally, on a personal level, many of us should interrogate whether our "impartial expertise" hinged on our relative distance and perceived invulnerability to past risks, in sharp contrast to the visceral fear now that our own homes and loved ones are equally at stake. At the end of the day, we were wrong to ever imagine global health as a technocratic oasis. It is—and has always been—political to its very core. And our refusal to engage on those terms in the past now finds many of us yelling futilely from the sidelines, just when it matters most.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Think Global Health is an editorially-independent online magazine, and it receives funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, which is mentioned in the eighth paragraph of this story. This story was updated on July 10, 2020 from an earlier version that gave the wrong name of the web site covid-local.org in the same paragraph.