Originally published on February 12, 2025; Updated on March 12, 2025

On Wednesday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shared its latest update on consumer prices, showing that the average cost of a dozen large grade A eggs increased nearly $1 in a single month—to $5.89. February's price jump is the largest since 1980–even after adjusting for inflation and beats the record set by January's price data.

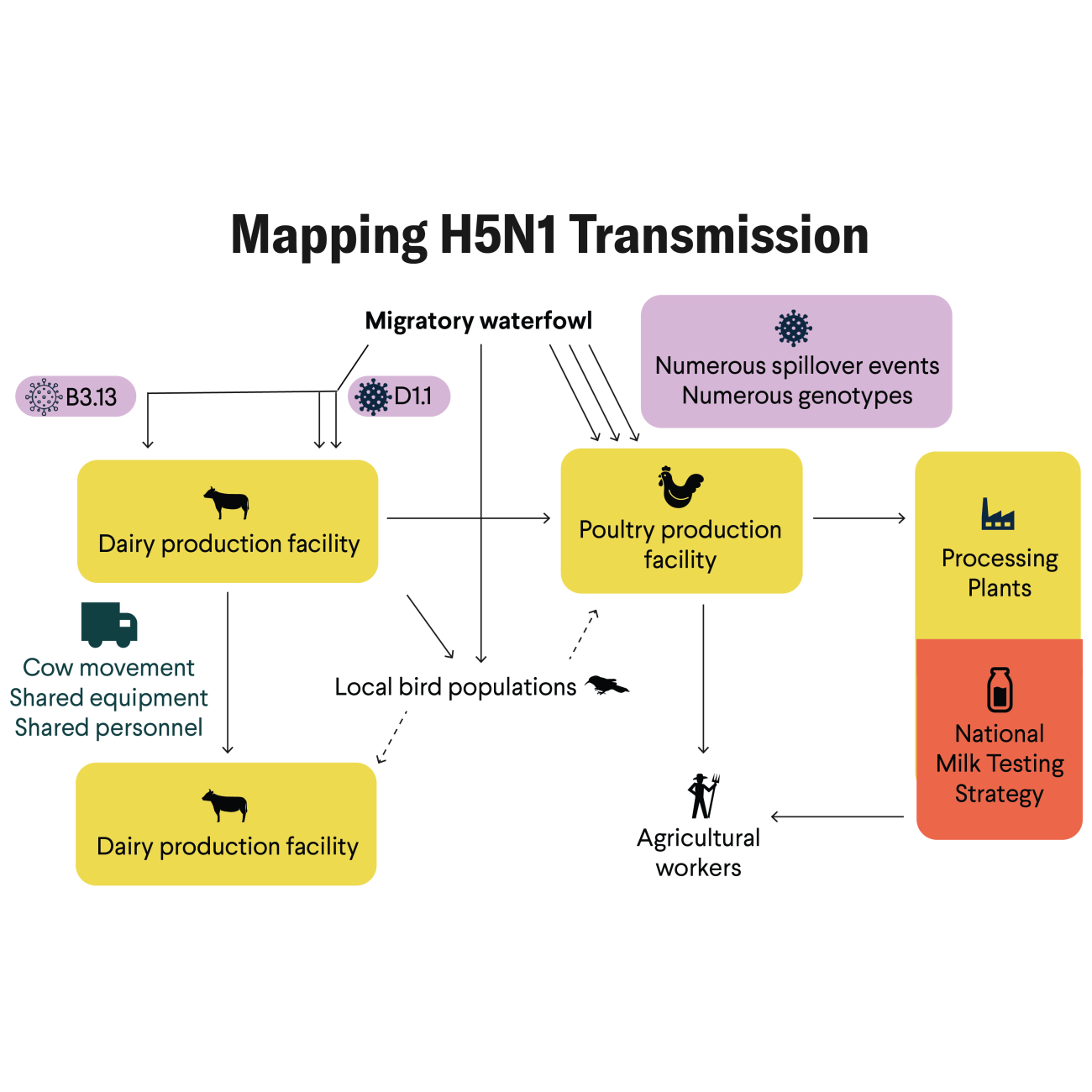

This historic run of egg-price surge stems from H5N1 avian influenza—or bird flu—hitting poultry producers hard this winter. The increase came after a new version of the virus emerged in wild migratory birds in September 2024 and then jumped to domesticated fowl.

"The main issue has been the emergence of a new genotype, the D1.1," said David Swayne, DVM, PhD, an avian influenza expert and private consultant who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for nearly 30 years. "It really has spread across all of [North America's] four migratory waterfowl flyways."

The D1.1 genotype has spilled not only into poultry, but also to humans and cows. It is behind November's severe flu case in British Columbia as well as the recent H5N1 death in Louisiana, the first in the United States. On January 31, the USDA announced that D1.1 had been detected in Nevada's milk supply, and the virus is suspected in a mild case recorded in one of the state's dairy workers. In mid-February, D1.1 hospitalized the owner of an infected backyard poultry flock in Wyoming. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported as of March 1.

The arrival of D1.1 could signify a turning point in the H5N1 outbreak. From December through February, owners of commercial, backyard, and hobbyist chicken flocks had to cull 53.8 million birds because of influenza exposure—nearly four times more than the same period last year. The past three months are the most destructive stretch of the North American outbreak, which initially arrived three years ago via migrating wild birds from Europe. Public health experts say it's time to defend against new spillovers between species.

"If you are the farmer, I'm sorry. The statistics don't count how devastating it is for them. It's devastating to have to put your animals down," said Rocio Crespo, a professor and poultry veterinarian at North Carolina State University.

In the United States, most egg-laying farms maintain fewer than 100 chickens, but large producers can house more than 100,000. Broiler farms for raising chicken meat average about 40,000 chickens, with large operations carrying more than 500,000.

Imagine culling one of those farms; the bodies stacked up. It takes an emotional and physical toll.

Yet hope remains because the overwhelming majority of bird flu outbreaks since 1959 have been eliminated by deploying biosecurity, disease surveillance, and vaccines. Relief could also be on the way as the new administration rolls out its response and the seasons shift. In late February, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins released a five-step plan to reduce egg prices, including a $100-million pledge for developing vaccines and therapeutics.

During the second half of February, egg producers recorded relatively less devastation—except for a large-scale outbreak affecting 3.2 million birds in Ohio. Flu outbreaks among poultry tend to ease as temperatures warm and wild birds start their spring migrations, reducing the chances of avian flu passing into domesticated animals.

Which Eggs Tend to Cost More During a Bird Flu Outbreak?

Following the detection of H5N1 on a poultry farm, U.S. regulations call for commercial and backyard producers to cull any chicken potentially exposed, leading to mass stamping-out campaigns.

The farmers receive compensation and indemnity for these efforts, which hinge on their participation in biosecurity programs to reduce the chances of such outbreaks. Stamping-out campaigns are the cornerstones of avian influenza biocontrol, successfully eliminating 41 of 44 outbreaks since 1959, as Swayne co-cataloged in a 2023 special report to the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) about global strategies for fighting bird flu [PDF]. These campaigns are expensive—the USDA recently stated that from January 2022 to November 2024, before the arrival of D1.1, the costs associated with the ongoing outbreak exceeded $1.4 billion, including $1.25 billion in indemnity and compensation payments.

According to USDA market analysis, of the chickens culled since the start of December 2024, 43.3 million were egg laying hens. Already this calendar year, culling has removed about 1 in every 8 conventionally caged hens used to produce eggs. For nonorganic cage-free hens, the number is 1 in every 13. Ohio, the nation's second-largest producer of eggs, has been hit hardest in 2025, accounting for 44% of egg layer losses.

"It's really low-income households that bear the brunt of any [egg] price increases because they spend a significant higher portion of their disposable income on food," said David Ortega, the Noel W. Stuckman Chair in Food Economics & Policy at Michigan State University.

Ortega's team studied how highly pathogenic bird flu influenced poultry prices from 2005 to 2023, namely, the cost of chicken meat, eggs, and turkey. All of these prices rose during outbreaks, the researchers reported last summer in Poultry Science, but the price effect on eggs was more intense.

Of note for people planning their food budgets, the team found that the price of cheaper conventional eggs rose much faster than that of the premium brands selling organic or free-range eggs. The trend comes from financially well-off people passing on their expensive eggs and opting for lower-budget options.

"As prices increase because of the shock of bird flu, the people who were buying the expensive eggs switch to the conventional eggs," Ortega said. "There is an increase in the relative demand, which is why you tend to see the price increase in the conventional products."

The reason egg prices more acutely feel the bird flu carnage stems from simple trends in supply and demand—but also the differing lifecycles of chickens in the food industry. Consumer demand for eggs is inelastic, meaning that people buy the products even when prices change. If the supply shrinks—meaning fewer eggs in stores—but consumer demand stays the same, the price will go up.

On the lifecycles, a chicken raised for meat consumption is ready after a month and a half, Crespo said. For egg laying hens, five months can pass before they can begin producing. It just takes much longer to replace egg layers and recover the supply.

The USDA stated the scarcity caused by the bird flu could be abating in a market analysis released on March 7:

Demand for shell eggs continues to fade into the new month as no significant outbreaks of HPAI [highly pathogenic avian influenza] have been detected in nearly two weeks. This respite has provided an opportunity for production to make progress in reducing recent shell egg shortages. As shell eggs are becoming more available, the sense of urgency to cover supply needs has eased and many marketers are finding prices for spot market offerings are adjusting downward in their favor. Shoppers have begun to see shell egg offerings in the dairycase becoming more reliable although retail price levels have yet to adjust and remain off-putting to many.

The arrival of Easter, the USDA predicts, could also convince sellers to lower prices or risk discouraging consumers. According to Politico, as of early March, the U.S. Department of Justice is investigating egg companies for price-fixing.

Remember 1996 and 2020

Last year, H5N1 became infamous in the United States as the country ushered in the world's first recorded infections in cattle as well as a slew of human cases, most of which were mild. Anyone trying to understand how the country reached this moment should consider two other key years in the evolution of avian influenza.

The first is 1996, when the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus was first identified in domestic geese in southern China. Scientists group avian influenza strains by their genetics but also by the harm they generate in chickens. High pathogenicity, or HPAI, means the strains cause disease in chickens; low pathogenicity, or LPAI, refers to mild strains. H5N1 is a strain of influenza A—one of more than 130 identified in nature.

H5N1 is a strain of influenza A—one of more than 130 identified in nature

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Historically, avian influenza strains followed an evolution pattern, beginning as mild LPAI in wild aquatic birds. Because these infections were harmless, the aquatic birds could carry the viruses over long distances during migrations, spreading them to other wild birds. Eventually these harmless strains would find their way into chickens or turkeys, where they would adapt to become much more dangerous, or highly pathogenic.

H5N1 changed this pattern. Suddenly this highly pathogenic strain and its closely related cousins—sometimes known collectively as H5Nx or H5—could travel hundreds and thousands of miles inside migratory aquatic birds. When those wild birds defecate near farms or steal feed, they can expose domesticated animals to influenza.

"The issue is that China has a huge population, a huge rural farm culture. And they have a lot of live market systems that produce birds for the live market," said Swayne.

Those live markets, where different animals live in adjacent cages, allow the virus to jump between species and adapt new features. Each time this strain infects a bird, human, or any animal, it changes genetically, and some of those mutations create new abilities. Some offshoots will spread more easily. Others will generate more grave symptoms.

After 1996, H5N1 remained relatively low key, occasionally sparking severe outbreak on farms and cases in humans. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 954 human cases of H5N1 have been recorded globally since January 2003; nearly half—464—proved fatal.

The next pivot point for H5N1 came in October 2020, when the natural course of adaptation and mutations generated a new subfamily—or clade—called 2.3.4.4b. As Swayne and his coauthors explained, 2.3.4.4b is highly infectious in domestic and wild ducks, "requiring only small virus doses to produce infections with the virus shedding over more than 14 days."

This adaptation allowed clade 2.3.4.4b to rapidly spread from Central Asia to East Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. By November 2021, it crossed into Newfoundland from Europe, leading to a flurry of avian outbreaks in the United States and Canada.

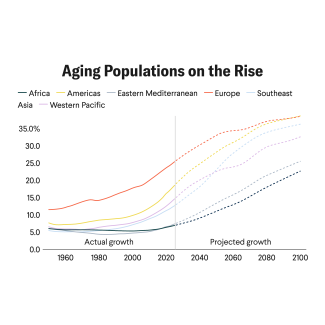

As of writing, approximately 550 different bird species and 83 mammalian species have caught H5Nx viruses.

Will the United States and Other High Income Countries Vaccinate Against Bird Flu?

USDA writes that of the $1.25 billion in indemnity and compensation payments paid to farmers during the ongoing bird flu outbreak, approximately $227 million went to facilities infected multiple times. The trend spotlights the difficulty of using standard biosecurity to control clade 2.3.4.4b.

These biosecurity measures developed over the last 60 years to swiftly detect avian influenza and prevent the virus's movement from farm to farm within a region. In high-income countries, these activities rely on public-private partnerships to deploy testing and resources, with the goal of depopulating any affected farm within 24 hours.

Low- or middle-income countries rely on vaccination to protect their poultry

The United States has a National Poultry Improvement Plan to help farms establish biosecurity plans and test for a variety of diseases. Keeping flu out of those chickens requires identifying all the ways the virus can breach a farm. Infected wild birds can fly over the fences, drawn by the chicken feed. Farmers can accidentally track tainted droppings into a hen house.

Early detection is crucial, and Swayne said farms in the United States, Australia, Canada, the European Union, and New Zealand rigorously monitor their hen houses and broilers for any signs of illness. During a typical week on a farm, about 1 in 1,000 chickens will die from natural causes, or 0.1%. Crespo, from North Carolina State University, said disease surveillance is sensitive enough to detect when this mortality rate rises to 0.3%.

Low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) have historically had fewer resources for flu surveillance and compensation, so they rely on vaccination to protect their poultry. Swayne said for those countries—Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Guatemala, Mexico, and Vietnam—it is a matter of preventing starvation because they depend on chickens for sustenance.

Yet saving their domestic food supply has long come with a downside: it is harder to sell their poultry in international trade. Even though high-income countries routinely vaccinate their poultry to fight infections like Newcastle Disease, they have often branded the use of avian influenza vaccines as an admission of guilt.

Among high-income countries, there is a long held belief that if you vaccinate against avian influenza, you're hiding infection. Some critics argue the flu vaccines are too leaky, meaning even though the shots prevent deaths, the chickens can still carry "silent" infections and spread the virus. Swayne said most of these objections are based on misinformation.

"If you look at experiments that replicate what happens in the field, when you vaccinate birds and you put them in contact with infected birds, they usually don't get infected, and the virus doesn’t spread at all," Swayne said. "Vaccination has no negative impact on the wholesomeness or the consumability of the product."

Because of H5N1's devastation, high-income countries could be shifting their positions on avian influenza vaccination. France began vaccinating its duck farms in October 2023 after 22 million domestic birds were culled during a single flu season two years prior. About a half dozen countries responded with import bans, though last month the United States and Canada eased their embargoes.

Swayne said if U.S. poultry producers decide to vaccinate against the flu, the best tactic would be to deploy the shots to the most susceptible farms or to secure certain sectors such as egg layers or megafarms. To ease international tension, the industry could also pledge not to use any flu vaccines in products destined for export.

"You can't feasibly vaccinate everything because it dilutes all your resources," Swayne said. "A risk-based targeted vaccination program would be much better in the United States."