European Union health ministers are meeting and communicating more frequently as COVID-19 spreads and the situation on the ground changes more rapidly. When they first met on Feb. 13, no viral deaths had been reported in Europe. By the time of their next meeting on Friday March 6, more than 4,000 cases had been confirmed across the EU. According to the latest figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in Stockholm, as of March 7th 213 deaths have been reported in the EU/EEA and the UK and the ECDC has raised the risk of coronavirus infection from moderate to high.

But there is also concern that not all member states are reporting responsibly. Italy has reported the highest number of deaths outside of China, it is the epicenter of the outbreak in Europe, and with Italy declaring a quarantine on the northern region of Lombardi, many people worry that what Italy is experiencing now will happen elsewhere in Europe. Some believe it is inevitable.

As some of the most well-equipped health systems in the world are starting to feel the strain the virus heaps on health systems, solidarity—a favourite theme in the European Union—is yet another victim of the epidemic. Requests from Italy to the other member states for assistance have so far gone unheeded, with one exception. The shortage of respiratory masks, gloves, protective suits, and sanitizing gels have led individual countries like Germany and the Czech Republic to ban the export of medical equipment. France is requisitioning all current and future stocks of protective masks for state agencies. This has raised the alarm not only among smaller countries hit by the virus but also raises issues about compliance with the rules of the single market.

Solidarity—a favourite theme in the European Union—is yet another victim of the epidemic

In an attempt to counteract this trend, the European Commission is aiming to trigger an emergency joint procurement process that allows it to purchase urgent medical supplies and to distribute those resources where most-needed across the Continent, even if capitals are reluctant to help each other. But not all member states are joining up. And an even larger agenda beckons: Germany and France want an initiative to bring medical production back to Europe, because it relies too much on imports from non-EU countries. For example, France imports about 40 percent of drug ingredients from China.

COVID-19 in the European Union is correctly perceived as a crisis, but it can turn into an opportunity if in confronting this deadly disease the region can overcome preexisting political and legal hurdles and find ways of working together. This is to some extent what happened after the chaotic handling of the 2009 pandemic of H1N1 (swine flu).To what extent will EU member states continue jealously guarding their primary responsibility for organizing and delivering health services and medical care within their own borders, while knowing all along, that the coordinated response for which the EU is responsible is desperately needed?

The EC Treaty Article 1525 provides a clear legal basis for interstate cooperation. It states that community action shall “complement national policies directed towards improving public health, preventing human illness and diseases, and obviating sources of danger to human health.”

Rapid response in times of crisis, however, is not a strength of this highly complex political construct

Under the Cross-border Health Threat Decision (2013), the European Commission coordinates with member states [PDF] through three key mechanisms: the early warning and response system, the health security committee, and the health security committee's communicators' network. Under these provisions the EC can also declare an emergency. The EC is supported in its work by relevant EU agencies, including ECDC, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Moreover, Member States' Joint Action Healthy Gateways, a Joint Action funded by the EU, is providing guidance and training. Another Joint Action called SHARP (strengthened international health regulations and preparedness in the EU) is helping to build laboratory capacity for outbreak preparedness. Many of these programs were set up or strengthened in the wake of H1N1, SARS and Ebola outbreaks.

Rapid response in times of crisis, however, is not a strength of this highly complex political construct. Indeed, for the European Union every crisis also becomes a test of the unique institution, as every move incites its critics. And some of the challenges faced because of COVID-19 go to the very core of the EU identity. The most important: will the EU be forced at some stage to abandon the 1985 Schengen Agreement that allows the members of the EU (and some associated countries such as Switzerland) free movement?

Will the EU be forced to abandon the 1985 Schengen Agreement that allows members of the EU free movement?

Populists in European parliaments are already using the coronavirus to reiterate their constant calls for national border controls and greater restriction of movement. Insidiously they are linking the immigration agenda with the outbreak agenda. This is being helped by the fact that presently thousands of refugees are trying to enter the European Union at the Turkish-Greek border as part of a Turkish political move to force EU leaders to come to its aid against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The coronavirus-fueled political debate is challenging many of the basic values that the EU maintains it is committed to – like the right to asylum.

As the Commission faces multiple deep crises simultaneously, everything at stake is also being touched by the virus. COVID-19 is feeding the EU’s economic slowdown. It is calculated that the EU’s intensive economic relations with China will lead to estimated export losses in the range of nearly $15.6 billion in 2020, of which the impact on the automotive industry alone will be about $2.5 billion. Even the Brexit negotiations have a viral dimension, as the UK (a strong global leader in health security) plans to leave the EU’s health protection system and take back control of its outbreaks as well. And on top of all this, the member states have to agree on a much lower EU budget because of the UK's departure.

In consequence the EU finance ministers are also contemplating a "coordinated fiscal response" later in March to protect against the economic fallout from the virus outbreak. The recommended steps, of course, will need to be decided at national level—and the present weakness of the government in both Germany and France can make agreements more difficult.

Meanwhile the EU has leveraged what it does best in times of crisis: coordinate all the actors that comprise the complicated EU architecture. While the European Commission has increased the level of its coordination to tackle the outbreak, the Croatian-led EU presidency decided on March 2 to escalate EU's response based on a mechanism known as Integrated Political Crisis Response arrangements.

Essentially, these are crisis meetings that bring together representatives of the office of the President of the European Council, the European Commission, the European External Action Service (EEAS), affected member states, and other relevant parties.

Last week the European Commission launched the interagency Corona Response Team, led by five commissioners who oversee the response around three main pillars: a) the medical field, b) mobility, from transport to travel advice and also to the Schengen-related open border questions, and c) the economy, looking in-depth at various business sectors—such as tourism, transport, trade, the supply and value chains, and at the broader macroeconomic picture.

The EU has 27 member states, 445 million citizens, and $16 trillion in GDP

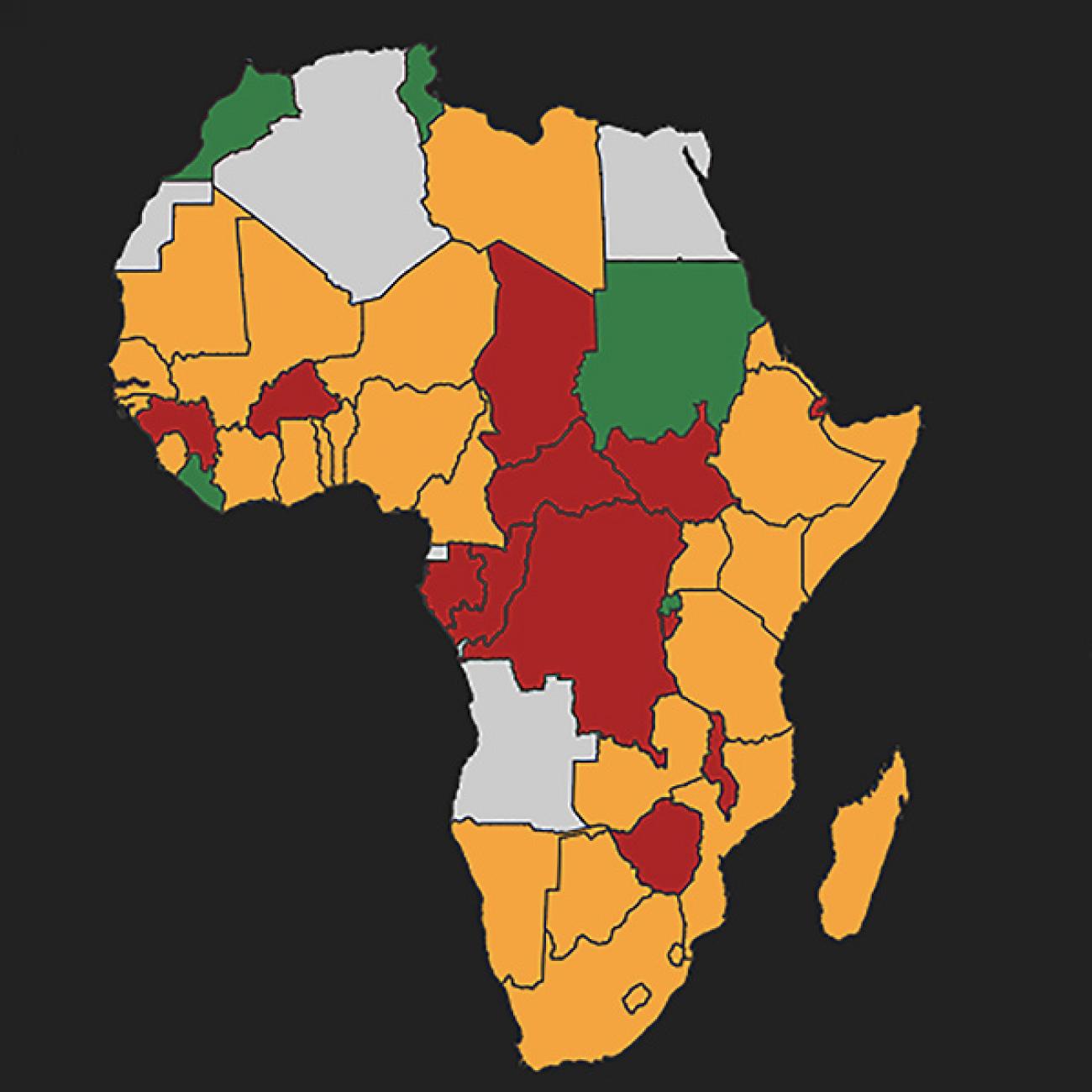

But Europe’s response cannot just be inward looking. Under its new president, the EU is attempting to increase its geopolitical footprint, being a powerful bloc of twenty-seven member states, 445 million citizens, and $16 trillion in GDP. For years, there have been calls for the European Union to be a global health leader—financially and politically. Now the EU has grasped the opportunity to show global responsibility in the face of COVID-19. Following the call of the WHO, it announced on March 2 a $252 million package in new funding to support the WHO in its work, as well as institutions in Africa and research related to diagnostics, therapeutics, and prevention.

On March 6 it announced an extra €37 million for new research to fight COVID-19. This will enable seventeen projects to tackle the outbreak on several fronts: vaccine development, diagnostics, treatment discovery, and the strengthening of medical systems. There is sure to be more money to follow. And as Germany prepares to take on the EU presidency as of July 1, there are high expectations for it to push to improve preparedness and crisis response both within and beyond the European Union, with a special view to the neighboring states and Africa and to act as a strong voice for global responsibility in the upcoming G7 and G20 meetings. The German Ministry of Health has already called for a stronger global role and more budget for the ECDC.

COVID-19 is highly political. Maybe the EU is lucky that in Ursula von der Leyen it has a president of the Commission who is both an experienced politician and a trained physician with a public health degree and has (in view of the upcoming presidency) strong links into the German government. Already now work can begin on strong Council conclusions addressing the issues at stake and strengthening the EU’s role in coordination—for example by strengthening the role of the ECDC. The world needs a strong political actor that is willing to protect global public goods for health and give strong support to the multilateral organizations such as the WHO. Making the world more prepared to deal with outbreaks is a good place to start.